Aging is a biological inevitability, but how we age is profoundly influenced by lifestyle choices. Among the most powerful interventions known to science, resistance training—also called weight training—stands out as one of the most effective ways to slow down the functional decline associated with aging. To understand why, we must first explore what aging does to the human body, and how lifting weights can counteract these changes at the molecular, cellular, and systemic levels.

The Physiology of Aging in Men

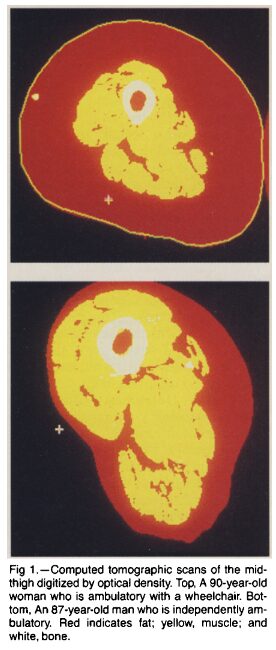

For men, the aging process is largely characterized by a progressive decline in anabolic hormones, particularly testosterone, growth hormone (GH), and insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1). This hormonal reduction leads to sarcopenia, or the gradual loss of muscle mass and strength. Studies show that men can lose up to 1% of muscle mass per year after the age of 30, accelerating after the fifth decade of life (Janssen et al., 2000).

Simultaneously, bone mineral density decreases due to lower mechanical loading and reduced testosterone levels, leading to higher risks of fractures and osteoporosis. Metabolic rate declines, visceral fat accumulates, and insulin sensitivity decreases—creating the perfect environment for metabolic syndrome, type 2 diabetes, and cardiovascular disease.

These processes are not just physical; cognitive performance and motivation are also affected. The combination of hormonal decline and muscle loss results in fatigue, low libido, and reduced vitality—a condition often referred to as andropause.

The Physiology of Aging in Women

In women, aging takes a distinctive hormonal pathway. The most abrupt transition occurs during menopause, marked by a sharp decline in estrogen and progesterone production. This hormonal shift disrupts calcium metabolism, leading to accelerated bone resorption and a dramatic increase in the risk of osteoporosis (Riggs et al., 2002).

Additionally, reductions in estrogen impact collagen synthesis, contributing to loss of skin elasticity, joint discomfort, and slower tissue repair. Muscle mass begins to decline in parallel with metabolic rate, often resulting in sarcopenic obesity—a state where body fat increases while lean mass decreases.

Beyond the visible effects, mitochondrial efficiency diminishes, oxidative stress rises, and inflammatory markers such as IL-6 and TNF-α become chronically elevated, accelerating cellular aging and increasing susceptibility to chronic disease.

What Is Resistance Training?

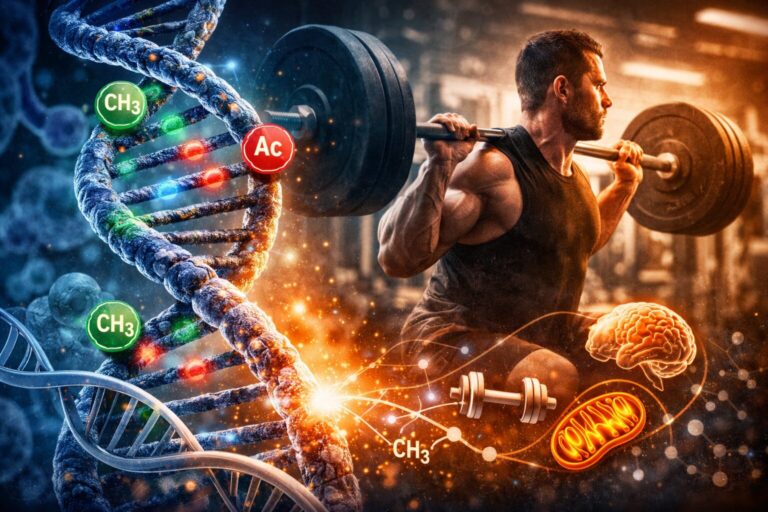

Resistance training (RT), also known as strength training or weight training, involves exercising muscles against an external load—such as dumbbells, barbells, resistance bands, or even one’s own body weight. This mechanical tension stimulates muscle fibers, primarily type II (fast-twitch) fibers, which are essential for strength and power and are the first to deteriorate with age (Lexell, 1995).

The principle is simple: by imposing a controlled stress on the musculoskeletal system, the body adapts by increasing muscle fiber size (hypertrophy), improving neural efficiency, and enhancing bone density. At a molecular level, RT activates the mTOR signaling pathway, promotes protein synthesis, and upregulates genes responsible for mitochondrial biogenesis and antioxidant defense (Burd et al., 2010).

The Anti-Aging Effects of Weight Training

From a scientific standpoint, resistance training is the most powerful non-pharmacological intervention for aging. It combats nearly every major physiological marker of decline:

- Prevents muscle loss (sarcopenia): Regular RT increases muscle protein synthesis, counteracting the catabolic effects of aging.

- Improves bone density: Mechanical loading stimulates osteoblast activity, strengthening the skeleton and reducing fracture risk.

- Enhances hormonal balance: RT has been shown to increase testosterone and growth hormone levels acutely, even in older adults (Kraemer et al., 1999).

- Boosts metabolism: Greater lean mass translates to higher resting energy expenditure, helping control body fat accumulation.

- Improves insulin sensitivity: Muscle tissue is the primary site of glucose uptake; more muscle means better glucose regulation.

- Reduces inflammation: Regular RT lowers systemic inflammation and oxidative stress, both central to the aging process.

- Supports mental health: Exercise-induced neurotrophic factors, such as BDNF, improve mood, memory, and cognitive performance.

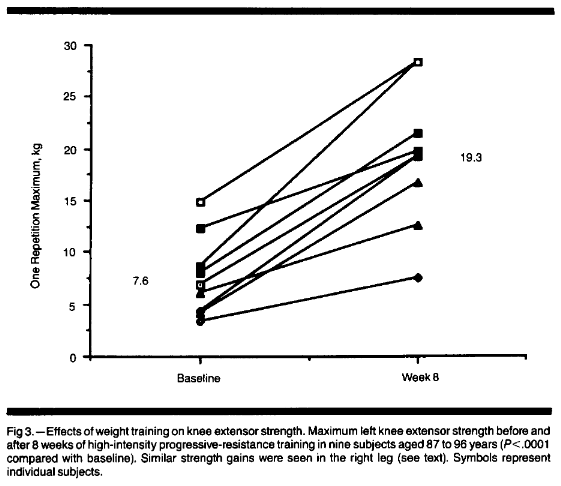

A meta-analysis by Peterson et al. (2010) found that adults over 50 who engaged in resistance training increased muscle mass by an average of 1.1 kg and significantly improved strength, regardless of sex or training experience. Another study by Fiatarone et al. (1990) demonstrated that frail nursing home residents—some in their nineties—achieved remarkable strength gains after only 10 weeks of progressive resistance training.

Why Starting Early Matters

While resistance training benefits people of any age, the earlier it becomes part of one’s lifestyle, the greater the long-term rewards. Beginning in your 20s or 30s establishes higher baseline muscle and bone density, providing a “reserve” that protects you later in life. As aging progresses, individuals who have trained consistently maintain mobility, independence, and resilience against injury.

Neuroscientific evidence also shows that the neuromuscular system adapts more efficiently at younger ages, making early training an investment that compounds over decades—physically, hormonally, and metabolically.

In contrast, delaying physical activity until later in life makes it harder to regain lost function. Although improvements are still possible, the rate of adaptation is slower due to reduced satellite cell activity and hormonal support. In simple terms: the sooner you start lifting, the slower you’ll age.

Aging Stronger, Not Weaker

The narrative that aging equals decline is outdated. Modern research supports the concept of “successful aging”—a process characterized by preserving physical function, cognitive capacity, and emotional well-being. And resistance training is the cornerstone of that success.

It’s not about building massive muscles; it’s about maintaining the ability to move, think, and live fully. Each squat, press, or pull is an act of defiance against entropy—an investment in the strength that defines your quality of life.

Forge Biology: Build Strength That Defies Time

At Forge Biology, we combine science, training, and nutrition to help men and women of all ages build stronger, healthier bodies—grounded in research and guided by data.

If you’re ready to understand how your biology can be forged into resilience, longevity, and performance, our personalized consultancy will design your program step by step—based on physiology, not guesswork.

Start today. Age is inevitable—weakness is not.

References

- Burd, N. A., et al. (2010). “Muscle protein synthesis in response to resistance exercise.” Journal of Applied Physiology, 108(4), 1360–1371.

- Fiatarone, M. A., et al. (1990). “High-intensity strength training in nonagenarians.” JAMA, 263(22), 3029–3034.

- Janssen, I., et al. (2000). “Skeletal muscle mass and distribution in 468 men and women aged 18–88 yr.” Journal of Applied Physiology, 89(1), 81–88.

- Kraemer, W. J., et al. (1999). “Hormonal responses to heavy-resistance exercise protocols.” Journal of Applied Physiology, 69(4), 1442–1450.

- Lexell, J. (1995). “Human aging, muscle mass, and fiber type composition.” Journal of Gerontology, 50A(Special Issue), 11–16.

- Peterson, M. D., et al. (2010). “Resistance exercise for muscular strength in older adults: A meta-analysis.” Ageing Research Reviews, 9(3), 226–237.

- Riggs, B. L., et al. (2002). “The pathogenesis of osteoporosis.” Endocrine Reviews, 23(3), 279–302.

Forge Your Mind. Build Your Biology.

Join the Forge Biology newsletter — where science meets strength.

Every week, you’ll get:

-

Evidence-based insights on training, performance, and recovery

-

Real analyses of supplements that work (and the ones that don’t)

-

Deep dives into hormones, nutrition, and human optimization

No fluff. No marketing hype. Just data-driven knowledge to build a stronger body — and a sharper mind.

Subscribe now and start mastering your biology.