1. What Is a Pre-Workout Meal or Supplement?

A pre-workout refers to any form of nutritional preparation consumed before exercise — whether that’s a balanced meal, a smoothie, or a formulated supplement. Its fundamental purpose is to fuel the body, optimize performance, and enhance recovery after the session.

In simple terms, a pre-workout strategy aims to provide substrates for energy production (carbohydrates and fats), amino acids for muscle protection, and key compounds that enhance focus, endurance, and power output. The timing is critical: the nutrients ingested before training directly influence your capacity to sustain intensity and delay fatigue.

2. What Are They For?

During exercise, the body undergoes a cascade of physiological stressors: increased energy demand, higher sympathetic activity, and amplified oxidative processes. The right pre-workout nutrition helps modulate those systems.

Carbohydrates raise blood glucose and muscle glycogen, preventing premature fatigue. Protein or amino acids reduce muscle protein breakdown. Hydration and electrolytes maintain fluid balance and neuromuscular efficiency.

Supplements, on the other hand, aim to amplify specific pathways. For example, caffeine stimulates the central nervous system and reduces perceived exertion; beta-alanine buffers lactic acid; and creatine phosphate supports rapid ATP regeneration.

In essence, pre-workout strategies are designed to help you train harder, longer, and more efficiently, while improving recovery kinetics after exercise.

3. What Do They Really Need to Have?

Despite marketing claims, most commercial “pre-workouts” are glorified caffeine cocktails. Scientifically, a good pre-workout — meal or supplement — needs only a few essential components:

- Energy substrate: typically 25–60 g of carbohydrates, depending on body mass and workout duration.

- Amino acid source: 15–25 g of protein (or equivalent essential amino acids).

- Hydration matrix: water and electrolytes, mainly sodium (300–600 mg) and potassium.

- Ergogenic compounds: optional, but supported by research — caffeine (3–6 mg/kg), creatine (3–5 g), and beta-alanine (2–5 g/day).

The nutrient timing window is flexible: 30 to 90 minutes before exercise is ideal to ensure digestion, nutrient absorption, and steady energy availability.

4. Different Kinds of Supplements as Pre-Workout — and Their Effects

a. Caffeine

The gold standard stimulant. It improves alertness, reaction time, and endurance by antagonizing adenosine receptors and increasing catecholamine release. Studies show performance benefits in both aerobic and anaerobic activities at doses of 3–6 mg/kg (Spriet, 2014).

b. Creatine Monohydrate

Although not an acute booster, chronic creatine supplementation (3–5 g/day) increases intramuscular phosphocreatine, improving power output and repeated high-intensity effort (Buford et al., 2007).

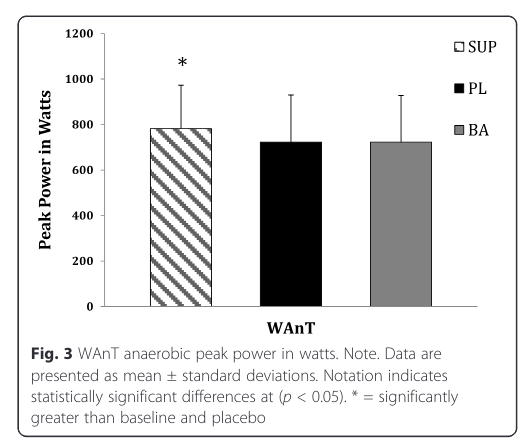

c. Beta-Alanine

Acts as a precursor to carnosine, buffering hydrogen ions that cause muscle acidosis. Effective for exercise lasting 1–4 minutes at doses around 4–6 g/day (Hobson et al., 2012).

d. Citrulline Malate

Enhances nitric oxide production, promoting vasodilation and improving nutrient delivery to muscles. Typical doses are 6–8 g about 60 minutes before exercise (Pérez-Guisado & Jakeman, 2010).

e. BCAAs or EAAs

Useful when training fasted; they can attenuate muscle protein breakdown and reduce perceived fatigue through central serotonin modulation (Jackman et al., 2010).

f. Nitrate-rich foods (like beetroot juice)

Boost nitric oxide pathways naturally, improving endurance and oxygen efficiency, particularly in submaximal exercise (Lansley et al., 2011).

In summary, only a few ingredients have robust scientific backing — caffeine, creatine, beta-alanine, and nitrates. Many others are either underdosed or poorly supported by evidence.

5. How to Do a Pre-Workout at Home

Building your own pre-workout is both simple and effective. You don’t need flashy labels — you need ingredients that work.

A homemade pre-workout meal can include:

- 1 banana (fast carbohydrate source)

- 1 scoop of whey protein (around 25 g protein)

- 1 teaspoon of instant coffee or 200 mg caffeine capsule (if tolerated)

- 500 ml of water with a pinch of salt (for sodium replenishment)

Optional:

- 3–5 g creatine monohydrate (daily, regardless of timing)

- 2 g beta-alanine (twice per day for saturation)

For those preferring solid food, oatmeal with whey and a small coffee works perfectly. The focus should always be digestibility and timing — you want to start your session energized, not heavy.

6. Final Statement

The fitness industry has turned “pre-workout” into a buzzword, but physiology remains simple. Your body doesn’t care if the energy comes from a commercial formula or from rice, fruit, and coffee — it only cares about substrates and readiness.

The goal is to enter training with enough available glycogen, balanced hydration, and a nervous system primed for performance. Whether that comes from a meal or a supplement depends on your schedule, tolerance, and personal goals.

Science is clear: there’s no magic powder that replaces consistency, nutrition, and rest. The most effective pre-workout is the one that keeps you training hard — every single day.

References

- Buford, T. W., et al. (2007). International Society of Sports Nutrition position stand: Creatine supplementation and exercise. Journal of the International Society of Sports Nutrition, 4(6).

- Hobson, R. M., et al. (2012). Effects of beta-alanine supplementation on exercise performance. Amino Acids, 43(1), 25–37.

- Jackman, S. R., et al. (2010). Branched-chain amino acid ingestion can ameliorate central fatigue during prolonged exercise. Journal of Nutrition, 140(3), 452–458.

- Lansley, K. E., et al. (2011). Beetroot juice and exercise performance: Physiological mechanisms and practical applications. Journal of Applied Physiology, 110(3), 591–600.

- Martinez, N., Campbell, B., Franek, M., Buchanan, L., & Colquhoun, R. (2016). The effect of acute pre-workout supplementation on power and strength performance. Journal of the International Society of Sports Nutrition, 13(1), 29.

- Pérez-Guisado, J., & Jakeman, P. M. (2010). Citrulline malate enhances athletic anaerobic performance and relieves muscle soreness. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 24(5), 1215–1222.

- Spriet, L. L. (2014). Exercise and sport performance with low doses of caffeine. Sports Medicine, 44(Suppl 2), S175–S184.

Forge Your Mind. Build Your Biology.

Join the Forge Biology newsletter — where science meets strength.

Every week, you’ll get:

-

Evidence-based insights on training, performance, and recovery

-

Real analyses of supplements that work (and the ones that don’t)

-

Deep dives into hormones, nutrition, and human optimization

No fluff. No marketing hype. Just data-driven knowledge to build a stronger body — and a sharper mind.

Subscribe now and start mastering your biology.