A summary of “The Physiology of Hunger” by Dr. Alessio Fasano, published in The New England Journal of Medicine (2025)

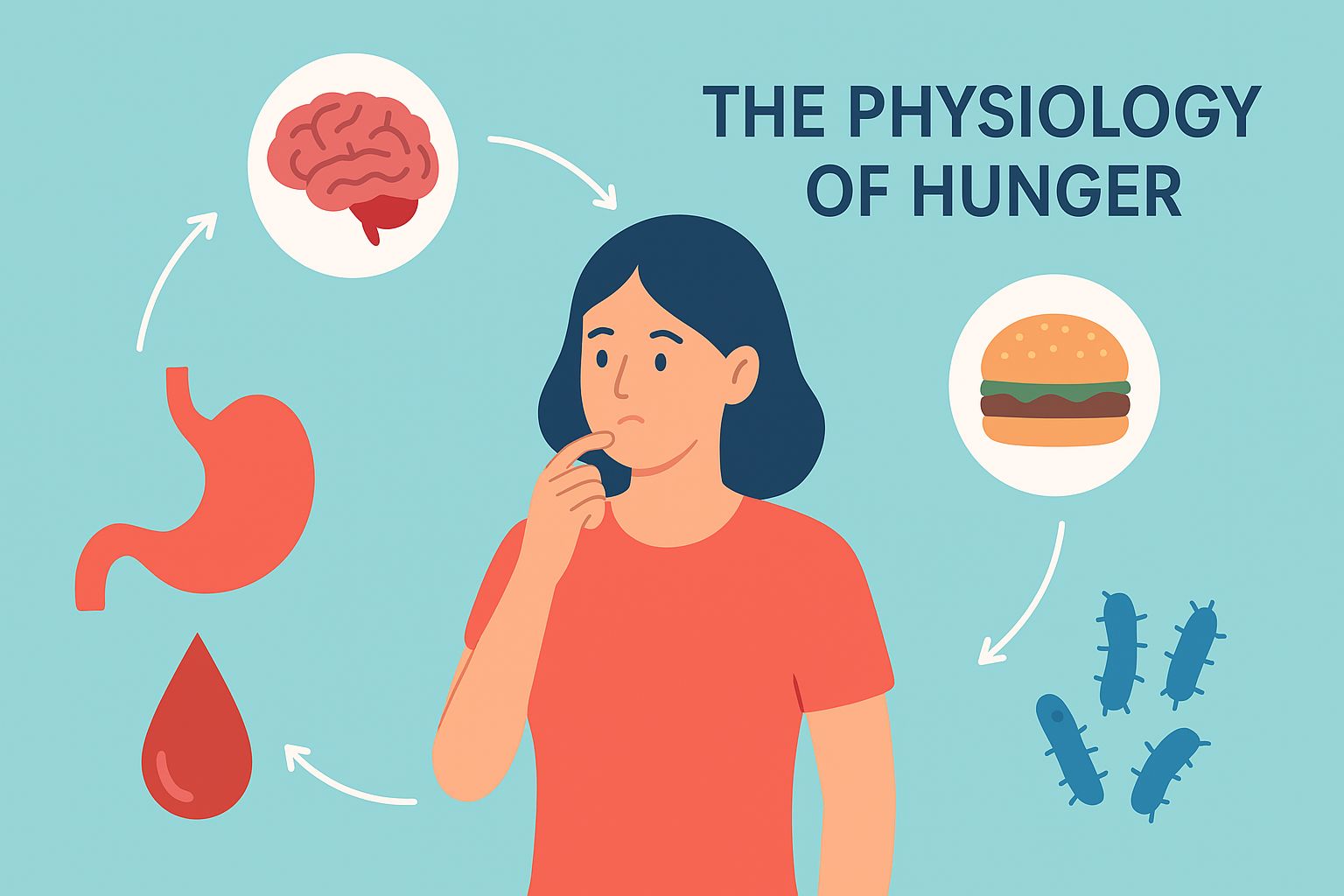

Why do we feel hungry — and why do we sometimes eat even when we’re not?

A recent scientific review by Dr. Alessio Fasano, published in the New England Journal of Medicine, dives deep into the fascinating biology behind hunger, explaining how our brain, gut, and even bacteria work together to control our eating habits.

In this post, we summarize and simplify that article — “The Physiology of Hunger” (N Engl J Med 2025;392:372–381. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMra2402679— to help you understand how hunger truly works.

🧬 Hunger: An Ancient Survival Instinct

Hunger is one of our oldest biological systems. For millions of years, it was essential for survival — a signal that told humans it was time to find food before starvation set in.

But around 12,000 years ago, agriculture changed everything. Food became easier to find and store. Over time, this abundance altered our physiology, making us vulnerable to a new kind of hunger: not just eating for survival, but eating for pleasure.

Dr. Fasano explains that while our ancestors’ bodies were “programmed” to overeat whenever food was available, this same instinct now contributes to obesity and metabolic diseases in a world of constant access to high-calorie foods.

⚙️ The Three Systems That Control Hunger

According to Fasano, hunger is not one single mechanism — it’s a complex dialogue between your brain, gut, hormones, and microbiome.

He divides it into three interconnected systems:

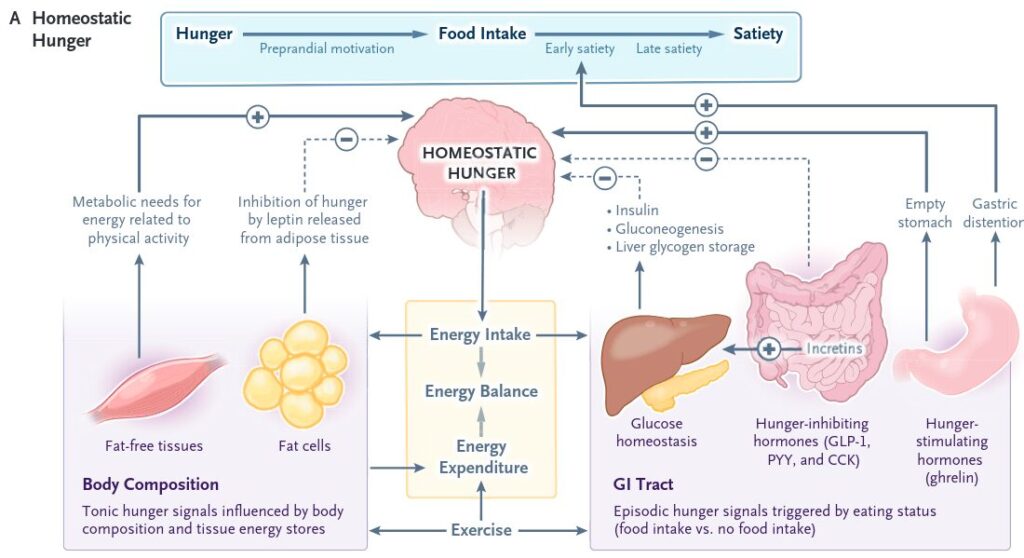

1. Homeostatic Hunger — When Your Body Truly Needs Energy

This is the original hunger — the physiological need to eat to restore balance.

It’s controlled by the brain–gut axis, especially the hypothalamus, which receives signals from the stomach and intestines.

When your stomach is empty, it releases ghrelin, the so-called “hunger hormone,” which tells your brain it’s time to eat. After a meal, hormones like GLP-1, PYY, and cholecystokinin (CCK) signal fullness.

This elegant system evolved to keep energy intake and expenditure in perfect sync — but it’s easily overridden in modern life.

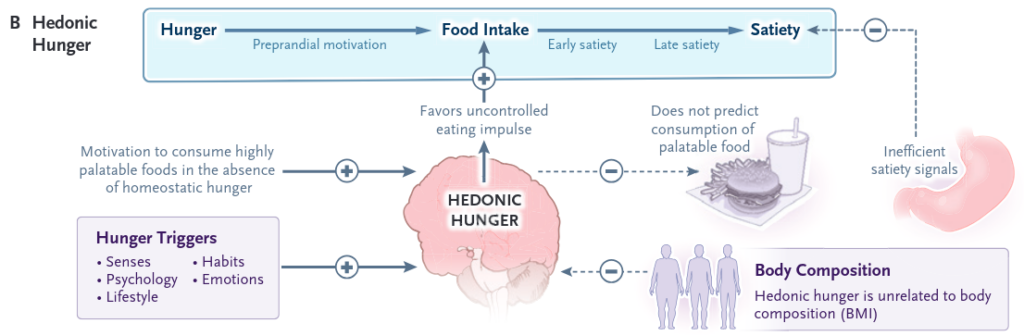

2. Hedonic Hunger — When You Eat for Pleasure, Not Survival

Ever found yourself reaching for dessert even though you’re full? That’s hedonic hunger.

This type of hunger is driven by dopamine, the brain’s pleasure chemical. It’s influenced by your emotions, habits, environment, and even advertising.

Dr. Fasano notes that in societies with abundant food, hedonic hunger has replaced homeostatic hunger as the dominant force.

We eat not because we need calories — but because food feels rewarding. This explains why sadness, stress, or even boredom can lead to overeating.

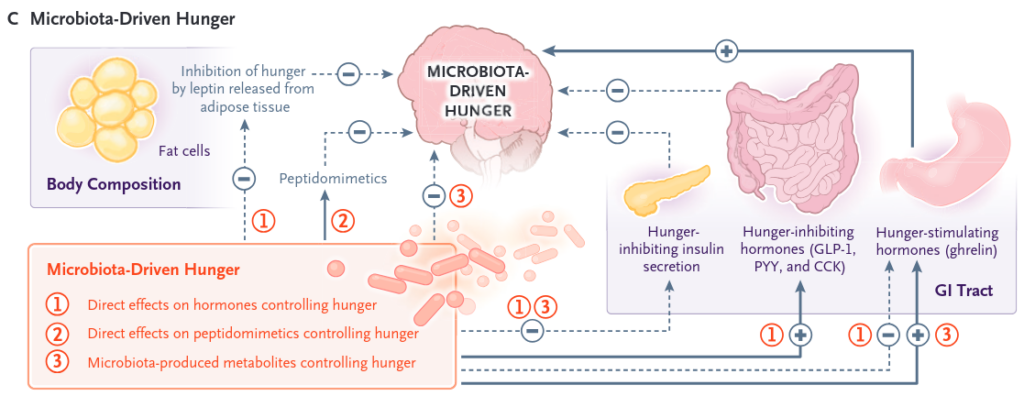

3. Microbiota-Driven Hunger — The Role of Gut Bacteria

The most cutting-edge part of Fasano’s paper explores how gut bacteria influence hunger.

Your microbiome — the trillions of microorganisms living in your intestines — can produce hormones, metabolites, and even molecular mimics that affect your appetite.

Some bacteria release compounds that act like leptin or PYY, hormones that suppress hunger. Others produce short-chain fatty acids (like butyrate or acetate) that influence insulin and ghrelin signaling.

In other words, your gut microbes may be helping — or sabotaging — your ability to control cravings.

⚠️ When Hunger Goes Off Track

When these systems lose balance, the results can be dangerous.

- Anorexia nervosa: Despite very high ghrelin levels, the brain becomes resistant to hunger signals. This leads to self-starvation and severe metabolic damage.

- Obesity: In the opposite extreme, hedonic and microbiota-driven hunger overpower homeostatic control, creating a cycle of overeating and weight gain.

According to the World Health Organization, 1 in 8 people worldwide had obesity in 2022, including over 390 million children and adolescents.

Fasano argues that these disorders are not just behavioral — they’re rooted in biology, evolution, and environment.

💊 The Promise and Peril of Modern Treatments

One of the biggest medical breakthroughs discussed in the article is the use of GLP-1 receptor agonists — drugs like semaglutide that mimic satiety hormones to reduce hunger and promote weight loss.

They can be life-changing for people with obesity or diabetes. But Dr. Fasano warns that non-medical use, especially among healthy teens or athletes, could have serious side effects — including hormonal imbalances and developmental risks.

🌍 Hunger in a Global Context

The article closes with a striking comparison:

While the United States spends over $800 billion every year on food and weight-related issues, the International Food Policy Research Institute estimates that $100 billion per year could end world hunger entirely.

This contrast, Fasano writes, shows how understanding the science of hunger isn’t just about health — it’s about justice, sustainability, and the future of food itself.

🔍 Final Thoughts

Dr. Alessio Fasano’s “The Physiology of Hunger” reminds us that hunger is far more than a feeling.

It’s a sophisticated, multi-layered system connecting our biology, psychology, and society.

By understanding how hunger truly works — from brain circuits to gut microbes — we can build better strategies for health, balance, and compassion in a world where both abundance and scarcity coexist.

Special Thanks

Special thanks to Dr. Renato Nogueira ,MD, for sharing this valuable article with Forge Biology,

Reference:

Fasano, A. The Physiology of Hunger. New England Journal of Medicine. 2025;392(4):372–381.

DOI: 10.1056/NEJMra2402679

Forge Your Mind. Build Your Biology.

Join the Forge Biology newsletter — where science meets strength.

Every week, you’ll get:

-

Evidence-based insights on training, performance, and recovery

-

Real analyses of supplements that work (and the ones that don’t)

-

Deep dives into hormones, nutrition, and human optimization

No fluff. No marketing hype. Just data-driven knowledge to build a stronger body — and a sharper mind.

Subscribe now and start mastering your biology.