Among all performance supplements ever studied, creatine monohydrate stands alone at the top. It is one of the most researched and proven ergogenic aids in sports science. Yet, one question still divides athletes and coaches:

Should you perform a loading phase or simply take a daily low dose from the start?

Let’s break down the physiology, the data, and the practical takeaways.

1. What the Loading Phase Means

A loading phase refers to consuming around 0.3 grams of creatine per kilogram of body weight per day—typically 20–25 grams daily—for five to seven days, divided into several doses.

This rapid, high-frequency intake quickly saturates muscle creatine stores, which normally takes several weeks to achieve with standard doses.

After the loading period, a maintenance dose of 3–5 grams per day is enough to keep muscle levels elevated.

In contrast, non-loading protocols skip the initial high intake and go straight to daily maintenance doses. The end result—full muscle saturation—is the same, but it takes longer to get there.

2. What Happens Inside the Muscle

Creatine acts as a phosphate reservoir. During intense muscle contractions, it donates phosphate groups to regenerate ATP, the immediate energy currency of cells.

Higher intramuscular creatine levels mean greater energy availability, shorter recovery times, and improved high-intensity performance.

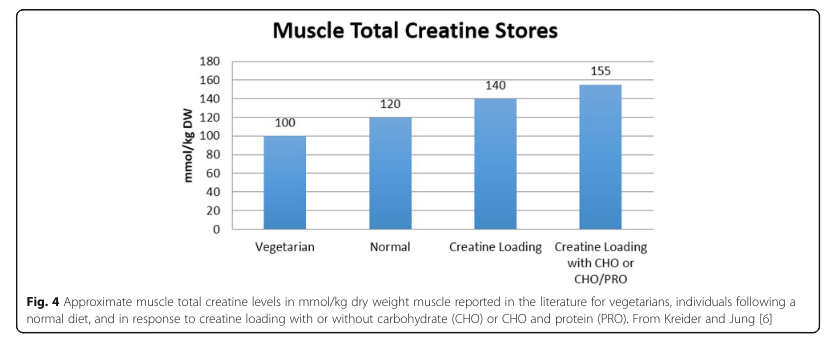

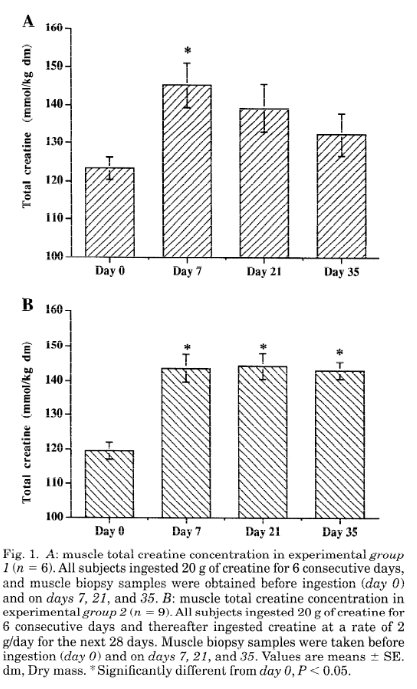

Studies using muscle biopsies have shown that loading protocols can increase total muscle creatine content by 20–40% in less than one week (Hultman et al., 1996). Without loading, similar increases occur only after three to four weeks of consistent use (Greenhaff et al., 1994).

3. Performance Outcomes: Loading vs. Non-Loading

Several controlled trials have compared both strategies:

- Hultman et al. (1996) demonstrated that a 6-day loading protocol (20 g/day) produced rapid increases in muscle creatine and performance in repeated sprint tests.

- Vandenberghe et al. (1997) confirmed that subjects who performed a loading phase achieved greater improvements in maximal strength and short-term power output after one week compared to those who used low daily doses.

- Rawson and Persky (2007) reviewed the topic and concluded that both approaches ultimately work, but loading provides faster results—a clear advantage for athletes preparing for short-term events or new training blocks.

When looking at long-term outcomes (8–12 weeks), both groups reach similar strength and hypertrophy levels once saturation is achieved (Kreider et al., 2017).

4. Is Loading Necessary?

Not necessarily. It depends on your priorities.

- If you want rapid performance gains—for example, before a competition or testing phase—loading is the efficient route.

- If you prefer a steady, simple approach, skipping the loading phase and taking 3–5 grams daily will get you to the same endpoint within about a month.

- In either case, creatine’s effects are cumulative and depend on consistent, long-term use, not acute timing.

Loading does not appear to increase side effects, but it may cause mild temporary water retention or gastrointestinal discomfort in some individuals. These effects subside once dosing is reduced to maintenance levels.

5. Practical Guidelines

| Goal | Recommended Dose | Duration | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Loading phase | 0.3 g/kg/day (~20–25 g) | 5–7 days | Divide into 3–5 servings with meals or carbs |

| Maintenance phase | 3–5 g/day | Continuous | Take any time of day; consistency is key |

| Skip loading | 3–5 g/day | 4 weeks to saturation | Same long-term outcome, slower start |

Taking creatine with carbohydrate or protein sources slightly improves uptake due to insulin-mediated transport (Green et al., 1996).

6. What Science Says About Safety

Creatine monohydrate is one of the safest supplements ever studied.

Decades of data show no harmful effects on kidney or liver function in healthy individuals.

The International Society of Sports Nutrition (ISSN) classifies it as “safe and effective for long-term use” (Kreider et al., 2017).

Concerns about dehydration or muscle cramps have been repeatedly disproven. In fact, creatine supplementation can improve hydration and thermoregulation under heat stress (Kavouras et al., 2009).

7. Final Takeaway

Both creatine loading and non-loading protocols work—the difference is speed, not outcome.

If you want rapid gains in strength, power, or training capacity, load for a week.

If you prefer simplicity, skip it and let your body saturate gradually.

Either way, creatine works. It’s one of the few supplements whose effects are consistent, predictable, and firmly supported by decades of science.

References

Green, A. L., Hultman, E., Macdonald, I. A., Sewell, D. A., & Greenhaff, P. L. (1996). Carbohydrate ingestion augments skeletal muscle creatine accumulation during creatine supplementation in humans. American Journal of Physiology, 271(5), E821–E826.

Greenhaff, P. L., Bodin, K., Soderlund, K., & Hultman, E. (1994). Effect of oral creatine supplementation on skeletal muscle phosphocreatine resynthesis. American Journal of Physiology, 266(5 Pt 1), E725–E730.

Hultman, E., Söderlund, K., Timmons, J. A., Cederblad, G., & Greenhaff, P. L. (1996). Muscle creatine loading in men. Journal of Applied Physiology, 81(1), 232–237.

Kavouras, S. A., Arnaoutis, G., Garagouni, C., Nikolaou, E., Pichard, C., & Sidossis, L. S. (2009). The effect of creatine supplementation on hydration status and heat tolerance in men exercising in the heat. Journal of Athletic Training, 44(5), 411–417.

Kreider, R. B., Kalman, D. S., Antonio, J., Ziegenfuss, T. N., Wildman, R., Collins, R., Candow, D. G., Kleiner, S. M., Almada, A. L., & Lopez, H. L. (2017). International Society of Sports Nutrition position stand: Safety and efficacy of creatine supplementation in exercise, sport, and medicine. Journal of the International Society of Sports Nutrition, 14(18), 1–18.

Rawson, E. S., & Persky, A. M. (2007). Mechanisms of muscular adaptations to creatine supplementation: Review article. Molecular and Cellular Biochemistry, 244(1–2), 89–94.

Vandenberghe, K., Goris, M., Van Hecke, P., Van Leemputte, M., Vangerven, L., & Hespel, P. (1997). Long-term creatine intake is beneficial to muscle performance during resistance training. Journal of Applied Physiology, 83(6), 2055–2063.

Forge Your Mind. Build Your Biology.

Join the Forge Biology newsletter — where science meets strength.

Every week, you’ll get:

-

Evidence-based insights on training, performance, and recovery

-

Real analyses of supplements that work (and the ones that don’t)

-

Deep dives into hormones, nutrition, and human optimization

No fluff. No marketing hype. Just data-driven knowledge to build a stronger body — and a sharper mind.

Subscribe now and start mastering your biology.