Protein is not just another nutrient — it is the physical and biochemical architecture of life. Every strand of muscle, every enzyme, and every hormone depends on protein. While carbohydrates and fats mainly serve as energy substrates, proteins are the builders and repairers. They define your body composition, influence your metabolism, and protect your health at every stage of life. Understanding protein is therefore not a diet trend — it’s a prerequisite for understanding how your body functions.

1. What Are Proteins?

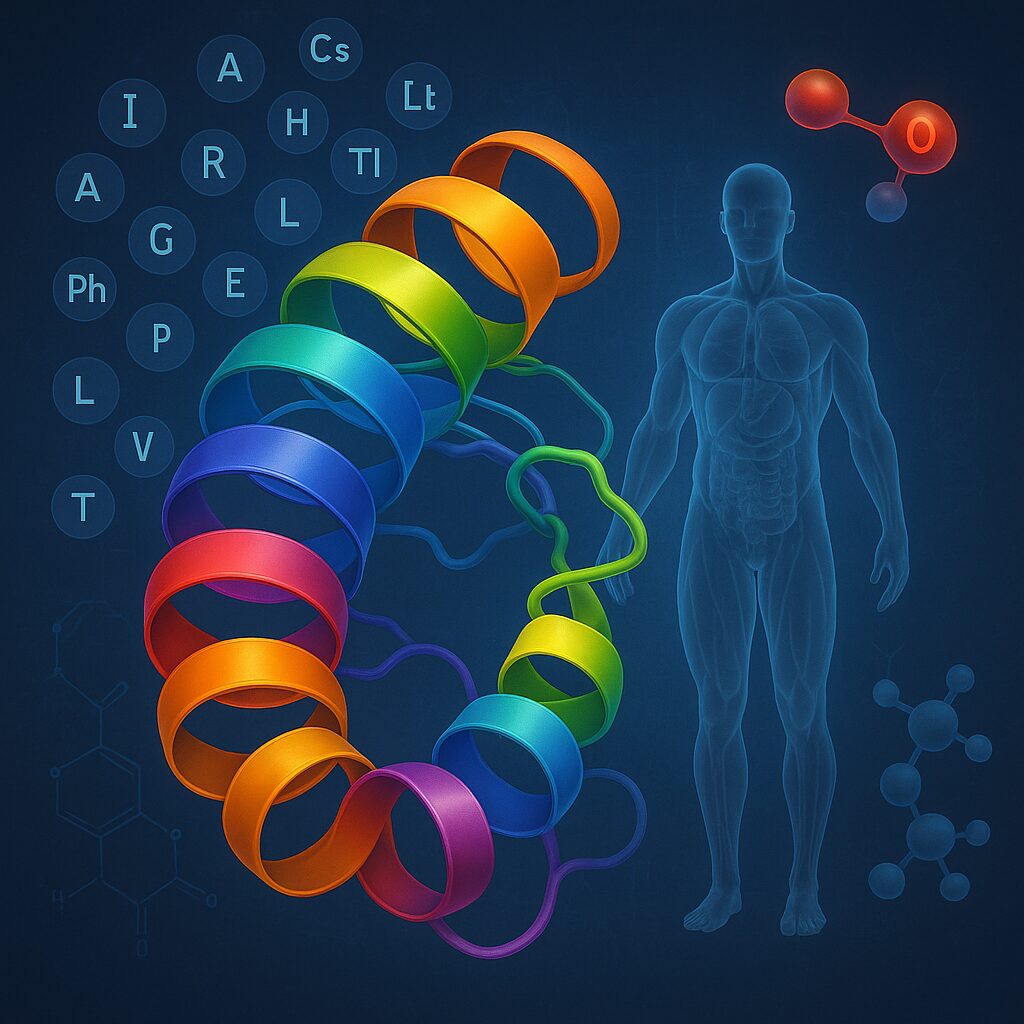

Proteins are macromolecules made up of amino acids — the “letters” that write every biological story inside your cells. Of the twenty amino acids that exist, nine are essential, meaning your body cannot synthesize them. You must obtain them from your diet. Each protein is formed by specific amino acid sequences that determine its three-dimensional structure and function. From hemoglobin carrying oxygen to collagen maintaining your skin’s elasticity, the diversity of protein roles is almost infinite.

The name “protein” originates from the Greek proteios, meaning “of prime importance,” and that is precisely what it is. Around 15–20% of the human body is made of protein, forming the foundation of muscles, organs, hair, and connective tissue. Every second of every day, proteins are being synthesized and degraded in a process called protein turnover. Life depends on this constant renewal.

2. Protein Metabolism: Building and Repairing

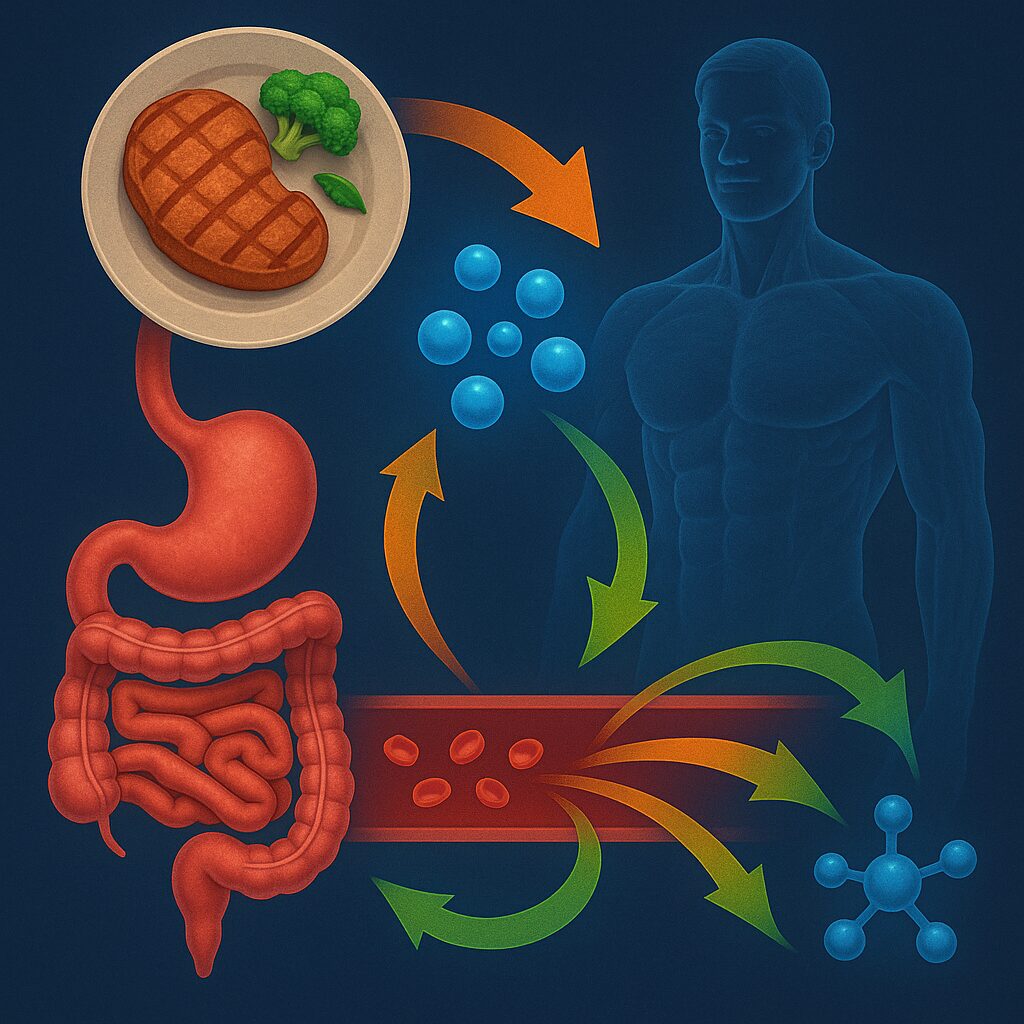

When you eat protein, digestive enzymes break it into amino acids, which enter the bloodstream and are distributed throughout the body. Inside cells, these amino acids are reassembled into new proteins based on your physiological needs. This dynamic process supports everything from healing wounds to building new muscle tissue after a workout.

The body cannot store protein the way it stores fat or glycogen, so daily intake is critical. If insufficient protein is consumed, the body starts breaking down muscle to liberate amino acids — leading to muscle loss, slower metabolism, and weakened immunity. Adequate protein not only maintains muscle mass but also fuels recovery, performance, and cellular regeneration.

3. Sources of Protein

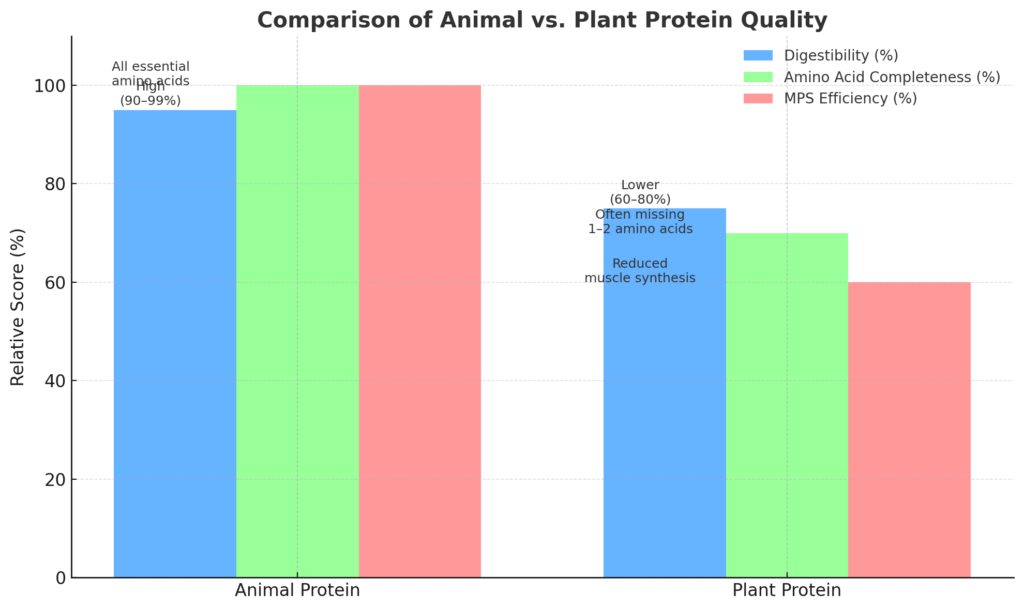

Proteins come from both animal and plant sources. Animal proteins include meat, poultry, fish, eggs, and dairy. These sources are considered “complete” because they contain all nine essential amino acids in the proper proportions needed for human physiology. Plant sources — like beans, lentils, nuts, seeds, and grains — can also provide protein, but they often lack one or more essential amino acids, or have poor digestibility due to fiber and antinutrients such as phytates and tannins.

Combining certain plant foods (for example, rice and beans) can form a complete amino acid profile, but it requires careful planning and larger portions to match the biological efficiency of animal protein. For athletes or individuals with higher protein demands, animal sources remain the most effective and practical solution.

4. Protein’s Role in the Body

Protein does much more than build muscle. It forms enzymes that catalyze biochemical reactions, hormones that regulate metabolism, and antibodies that protect against infection. Structural proteins such as collagen and elastin maintain tissue integrity, while contractile proteins like actin and myosin enable movement. Protein is the infrastructure, the messenger, and the machinery of your physiology.

Without sufficient protein, none of this happens efficiently. Your body cannot heal, your immune system weakens, and your metabolism slows down. This is why protein deficiency affects not only athletes but anyone whose diet is dominated by processed carbohydrates and low-quality fats.

5. Protein and Energy Metabolism

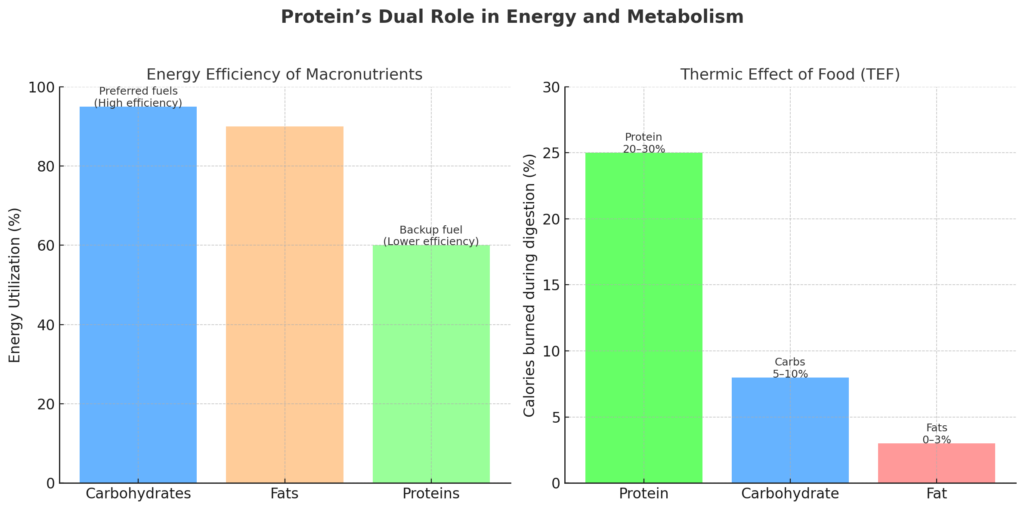

Although carbohydrates and fats are preferred energy sources, protein can serve as a backup during caloric restriction or glycogen depletion. Through gluconeogenesis, certain amino acids are converted into glucose to fuel the brain and muscles. However, this process is inefficient and can lead to muscle breakdown if dietary protein is inadequate.

Beyond its structural role, protein also has a high thermic effect of food (TEF) — your body burns roughly 20–30% of its calories simply digesting it. This means high-protein diets increase energy expenditure, improving fat loss and satiety while supporting lean tissue retention.

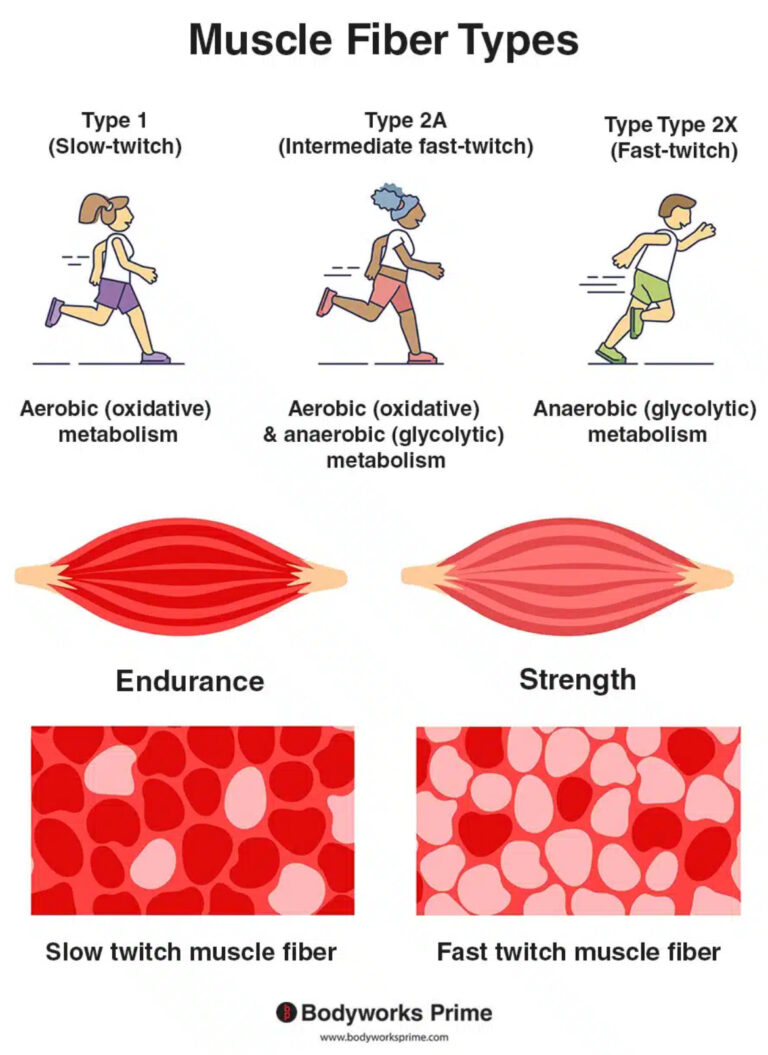

6. Why Protein Is Essential for Athletes

For anyone training regularly, protein is the cornerstone of adaptation. Exercise — especially resistance training — causes microscopic damage to muscle fibers. Protein provides the amino acids needed to repair these fibers, making them stronger. Without it, recovery and growth are compromised, and fatigue accumulates.

Athletes require more protein not just for muscle repair, but also for enzyme regeneration, red blood cell production, and immune function. Adequate intake minimizes soreness, accelerates recovery, and supports performance consistency. Quite literally, protein is what transforms training into progress.

7. Protein Requirements: How Much Do You Need?

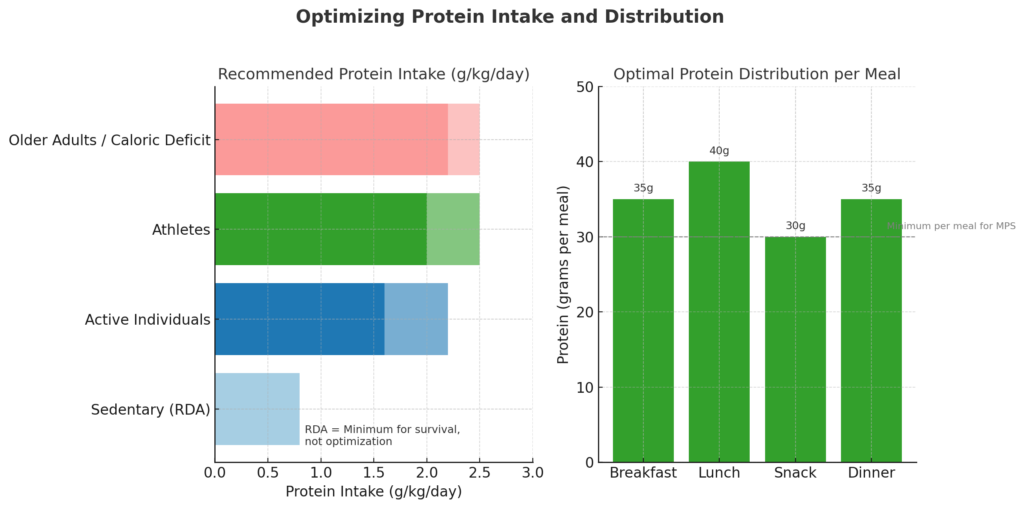

The general RDA of 0.8 g/kg/day prevents deficiency, not optimization. For those who train regularly, the scientific consensus supports 1.6–2.2 g/kg/day (Morton et al., 2018). Endurance athletes, older adults, and those in caloric deficit may benefit from even higher intakes, up to 2.5 g/kg/day.

Protein should be spread evenly across meals — approximately 30–40 grams every 3–4 hours — to maintain a positive nitrogen balance. This ensures a constant supply of amino acids for muscle protein synthesis (MPS). What matters most is consistency: daily, adequate intake over time.

8. Protein Timing and Distribution

While the “post-workout window” matters, it’s not everything. Consuming protein soon after training does support recovery, but research shows that total daily intake and distribution are far more important than exact timing.

Four balanced meals spaced throughout the day outperform two heavy meals, even with the same total protein. A slow-digesting protein like casein before bed can further support overnight repair. The takeaway: treat protein like hydration — frequent and steady, not sporadic.

9. Fast and Slow Proteins

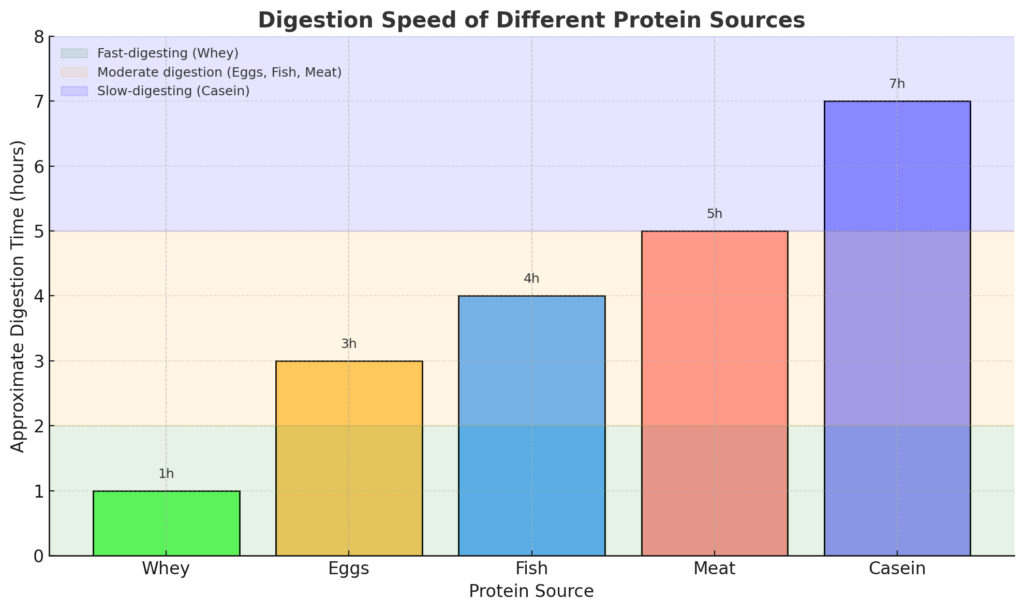

Different protein sources digest at different rates. Whey protein is absorbed quickly and is ideal post-workout, triggering a rapid spike in MPS. Casein, on the other hand, digests slowly, providing a sustained release of amino acids for several hours. This makes it perfect before long periods without food, such as sleep.

Eggs, meat, and fish fall somewhere in between, offering balanced digestion and nutrient density. The key is diversity — combining different absorption rates creates a more stable anabolic environment throughout the day.

10. The Role of Leucine

Leucine, one of the branched-chain amino acids (BCAAs), is the key signal that activates the mTOR pathway, stimulating muscle protein synthesis. Each protein-rich meal should contain at least 2.5–3 grams of leucine to maximize this anabolic effect.

Animal proteins — particularly whey, eggs, and meat — are rich in leucine. Plant proteins often fall short, which is why vegans must consume higher total protein or supplement with leucine-enriched blends. Without reaching the leucine threshold, muscle-building potential remains suboptimal.

11. Protein and Body Composition

Protein influences not just muscle gain, but also fat loss and overall composition. Its high thermic effect and ability to suppress appetite make it indispensable for anyone pursuing a leaner physique. Studies consistently show that diets with higher protein intakes result in better fat-to-muscle ratios, improved metabolism, and better long-term adherence (Wycherley et al., 2012).

Protein also stabilizes blood sugar levels and prevents the energy crashes that come from carb-heavy meals. It’s not simply a “macronutrient” — it’s a metabolic governor, regulating everything from hunger hormones to thermogenesis.

12. Protein and Cognitive Health

The brain depends on amino acids to produce neurotransmitters like dopamine, serotonin, and acetylcholine. Low protein intake impairs focus, emotional stability, and resilience to stress. For instance, the amino acid tyrosine supports dopamine production, improving motivation and alertness — essential traits for athletes and professionals alike.

A diet low in protein can lead to “brain fog” and irritability, especially when combined with caloric restriction. On the other hand, steady protein consumption stabilizes mood, enhances memory, and improves decision-making. Nutrition doesn’t just feed the body — it shapes the mind.

13. Myths About Protein

One of the most persistent myths is that high-protein diets harm the kidneys. In healthy individuals, there’s no scientific evidence supporting this claim (Antonio et al., 2016). The kidneys efficiently adapt to higher protein intake by increasing filtration rate without damage. Another myth suggests that the body can only absorb 30 grams per meal. In reality, while MPS peaks around that point, the rest contributes to other vital processes — nothing is wasted.

The idea that plant protein is “just as good” as animal protein is another misconception — one we’ll address in the next section. The biological truth is that all proteins are not created equal, and human physiology evolved on a diet rich in animal-sourced nutrition.

14. Protein Deficiency and Its Impact

Protein deficiency can manifest subtly — fatigue, hair loss, poor recovery — or severely, as in muscle wasting and immune dysfunction. Even slight deficiencies over time lead to loss of lean mass, hormonal disruption, and metabolic slowdown. Aging compounds the problem through anabolic resistance — the body’s reduced ability to utilize amino acids efficiently.

For older adults, protein becomes medicine. Maintaining strength and independence in later years depends largely on maintaining muscle mass, and that depends on sufficient, high-quality protein intake.

15. Protein and Longevity

Protein is strongly correlated with vitality and life expectancy when consumed appropriately. It maintains lean mass, preserves bone density, and improves metabolic health. While some epidemiological studies suggest that excessive intake of processed meats may increase certain risks, whole-food animal proteins — like eggs, fish, and lean meats — are associated with longevity and reduced disease markers (Levine et al., 2014).

In the aging population, higher protein intake prevents frailty and supports immune resilience. The science is clear: muscle is a biomarker of survival, and muscle depends on protein.

16. Animal vs. Plant Protein: The Biological Truth

While both animal and plant proteins provide amino acids, they differ dramatically in quality, digestibility, and bioavailability. Animal proteins — from meat, eggs, fish, and dairy — are complete, meaning they supply all essential amino acids in the right proportions and are easily digested (with digestibility scores of 90–99%). In contrast, most plant proteins lack one or more essential amino acids (commonly lysine or methionine) and contain fiber, phytates, and lectins that reduce absorption.

Beyond amino acid profiles, plant proteins are less efficient at stimulating muscle protein synthesis. Studies show that to match the anabolic effect of 25 grams of whey, one might need nearly double the amount of soy or pea protein — along with supplementation of missing amino acids (Phillips & van Loon, 2011).

Additionally, long-term vegan diets often require supplementation with vitamin B12, iron, zinc, and omega-3s — nutrients naturally abundant in animal foods but scarce in plants. Relying exclusively on plant proteins can therefore lead to nutritional deficiencies, reduced muscle mass, and hormonal imbalance over time.

From an evolutionary standpoint, humans are omnivores built to thrive on animal protein. Our digestive systems, enzymatic profiles, and metabolic pathways are adapted to it. While moderate plant protein intake is beneficial, animal protein remains biologically fundamental for optimal health, performance, and recovery. The more restrictive the diet, the greater the physiological compromise.

17. Key Takeaways

- Protein is the body’s primary building material — critical for muscle, immunity, and metabolism.

- Animal proteins are superior in amino acid balance, digestibility, and biological availability.

- Aim for 1.6–2.2 g/kg/day of total protein, distributed evenly across meals.

- Include leucine-rich sources post-training for optimal recovery.

- Plant proteins alone cannot fully support peak human physiology without supplementation.

18. Final Thoughts

Protein isn’t a trend — it’s a law of biology. It is the code that builds, heals, and sustains life. Every organ, every thought, every motion depends on it. To ignore its importance or replace it with inferior substitutes is to compromise the very machinery of your body.

Feed yourself with what evolution designed you to eat: complete, high-quality protein that fuels both body and mind. Train hard. Recover well. Eat intelligently. And remember — strength, vitality, and clarity all begin with the molecule that built you.

References

- Antonio, J., Ellerbroek, A., Silver, T., & Vargas, L. (2016). A high protein diet has no harmful effects: A one-year crossover study in resistance-trained males. Journal of Nutrition and Metabolism, 2016, 9104792.

- Levine, M. E., Suarez, J. A., Brandhorst, S., Balasubramanian, P., Cheng, C. W., Madia, F., … & Longo, V. D. (2014). Low protein intake is associated with a major reduction in IGF-1, cancer, and overall mortality in the 65 and younger but not older population. Cell Metabolism, 19(3), 407–417.

- Morton, R. W., Murphy, K. T., McKellar, S. R., Schoenfeld, B. J., Henselmans, M., Helms, E., … & Phillips, S. M. (2018). A systematic review, meta-analysis and meta-regression of the effect of protein supplementation on resistance training–induced gains in muscle mass and strength in healthy adults. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 52(6), 376–384.

- Phillips, S. M., & van Loon, L. J. C. (2011). Dietary protein for athletes: From requirements to metabolic advantage. Applied Physiology, Nutrition, and Metabolism, 36(5), 647–654.

- Wycherley, T. P., Moran, L. J., Clifton, P. M., Noakes, M., & Brinkworth, G. D. (2012). Effects of energy-restricted high-protein, low-fat compared with standard-protein, low-fat diets: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 96(6), 1281–1298.*

Forge Your Mind. Build Your Biology.

Join the Forge Biology newsletter — where science meets strength.

Every week, you’ll get:

-

Evidence-based insights on training, performance, and recovery

-

Real analyses of supplements that work (and the ones that don’t)

-

Deep dives into hormones, nutrition, and human optimization

No fluff. No marketing hype. Just data-driven knowledge to build a stronger body — and a sharper mind.

Subscribe now and start mastering your biology.