Introduction

Is cognitive decline an inevitable part of aging?

For decades, scientists believed that memory loss, slower reasoning, and mental fog were unavoidable as we grew older. But new research suggests otherwise.

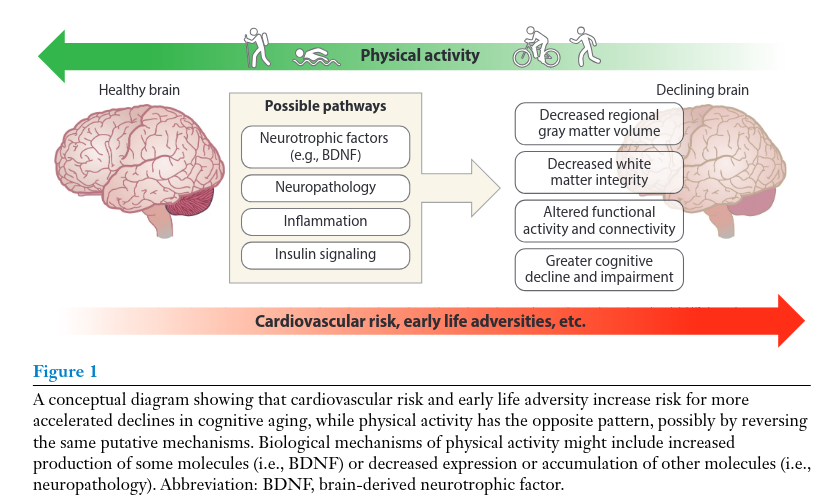

According to a major review published in the Annual Review of Clinical Psychology (2022), titled Cognitive Aging and the Promise of Physical Activity, the aging brain is far more adaptable than previously believed — and exercise may be one of the most powerful tools to preserve and even enhance cognitive function.

About the Study and Its Authors

The paper was written by Kirk I. Erickson, Shannon D. Donofry, Kelsey R. Sewell, Belinda M. Brown, and Chelsea M. Stillman, from the University of Pittsburgh (USA), Murdoch University (Australia), University of Granada (Spain), and Allegheny Health Network (USA).

These researchers specialize in neuropsychology, exercise physiology, and aging. Their shared goal: to uncover how movement, cardiovascular health, and brain plasticity interact to determine how we age — mentally and physically.

The Main Question: Can Exercise Reverse Cognitive Aging?

The study set out to answer a profound question:

Why do some people remain mentally sharp into their 80s while others experience cognitive decline decades earlier?

To solve this, the authors examined the interplay between:

- Genetics — such as APOE ε4 and BDNF polymorphisms that increase dementia risk.

- Early-life adversity — experiences that shape brain resilience across the lifespan.

- Cardiometabolic health — including obesity, hypertension, and type 2 diabetes.

- Lifestyle behaviors — especially physical activity, which may act as a protective shield for the brain.

Methodology and Scientific Approach

This work is not a single experiment but a comprehensive scientific synthesis of decades of data.

The authors reviewed evidence from:

- Longitudinal population studies, linking physical fitness to brain volume and function.

- Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) showing how aerobic and resistance training affect cognition.

- Neuroimaging and molecular research revealing exercise-induced changes in hippocampal size, blood flow, and neurotrophic factors (like BDNF).

- Animal studies, confirming that exercise promotes neurogenesis, angiogenesis, and reduced inflammation — the cellular hallmarks of a “younger brain.”

Key Findings: Exercise Is Cognitive Medicine

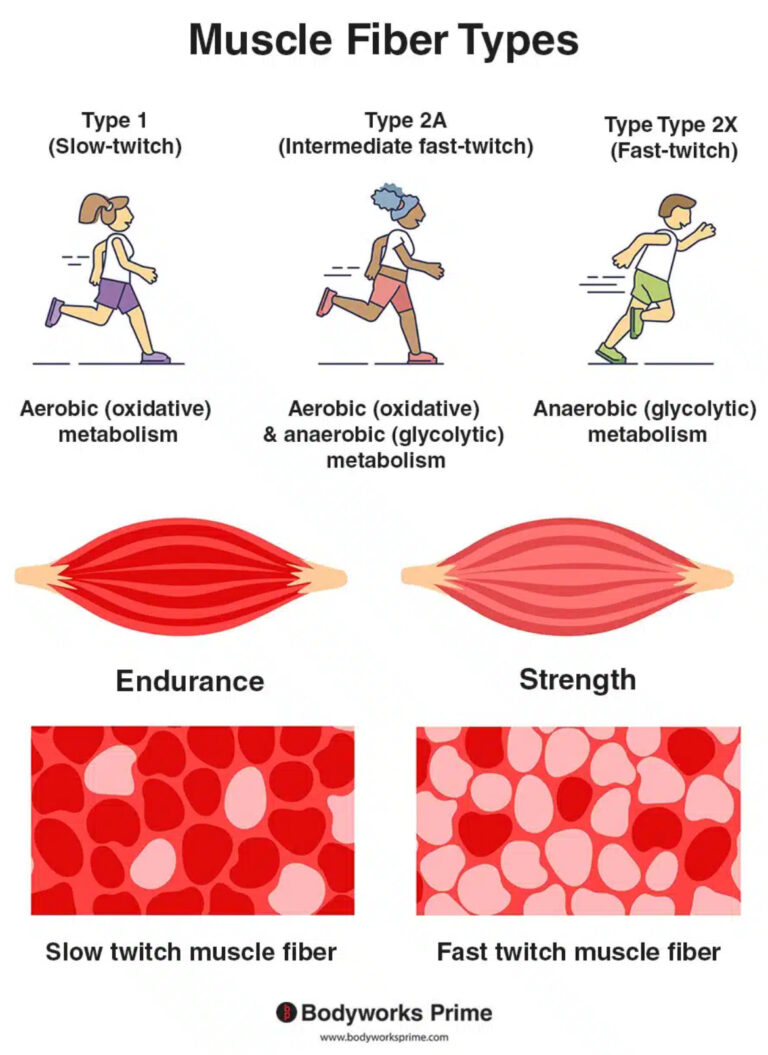

- Physical activity slows brain aging

People who exercise regularly exhibit slower cognitive decline, better memory, and stronger executive function. In fact, older adults who exercise can “reclaim” one to two years of hippocampal volume — effectively reversing part of age-related brain shrinkage. - The aging brain remains plastic

Exercise boosts brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), stimulates new neuron formation, and improves cerebral blood flow. These adaptations mirror the effects seen in “enriched environments” in animal studies — proving that even an older brain can adapt and grow. - Exercise combats dementia risk

Physically active individuals have up to 50% lower risk of developing Alzheimer’s or other dementias. Midlife exercise, in particular, is strongly linked to preserved brain volume and better cognitive resilience decades later. - Exercise interacts with genetics and lifestyle

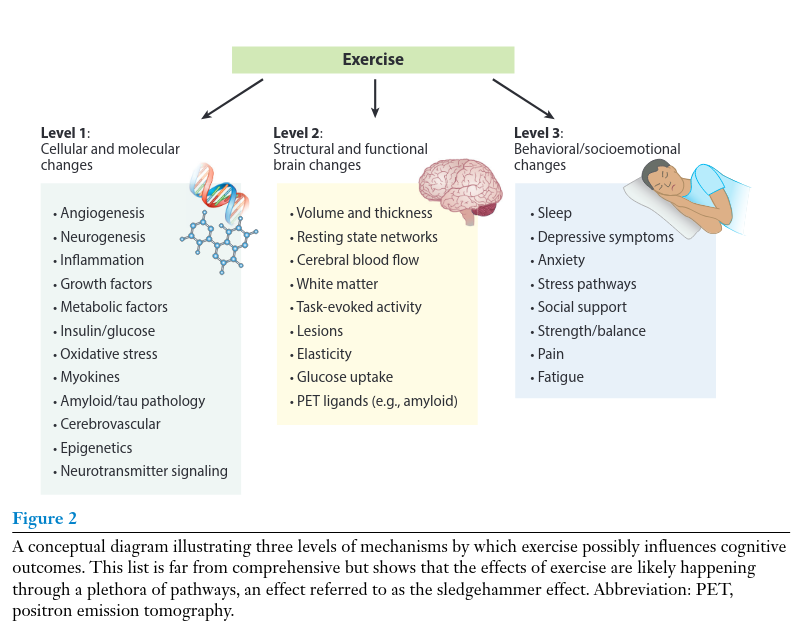

Even individuals with high genetic risk for Alzheimer’s (APOE ε4 carriers) benefit from regular activity, showing improved cognitive function and reduced amyloid-beta accumulation compared to sedentary peers. - Multiple biological mechanisms are involved

The authors describe a “sledgehammer effect” — meaning that exercise triggers dozens of beneficial molecular pathways at once:- Increased BDNF and growth factors

- Reduced inflammation and oxidative stress

- Enhanced insulin sensitivity and glucose metabolism

- Improved sleep and emotional regulation

Together, these effects make physical activity one of the most powerful systemic interventions ever studied for aging.

Beyond Muscles: How Exercise Shapes the Brain

Neuroimaging studies reveal that active individuals have larger hippocampi and prefrontal cortices, stronger neural connectivity, and higher resting-state efficiency.

These regions are crucial for memory, focus, and emotional regulation — the very areas most affected by aging.

At the molecular level, exercise enhances angiogenesis (growth of new blood vessels) and neurogenesis (birth of new neurons). This combination nourishes the brain and promotes resilience against stress and neurodegeneration.

Exercise as Preventive and Therapeutic Tool

The review highlights two key applications:

- Prevention:

Regular exercise in early and mid-adulthood can delay or even prevent the onset of neurodegenerative diseases. - Therapy:

In individuals with mild cognitive impairment or early-stage dementia, supervised exercise programs produce measurable improvements in executive function, attention, and daily living skills.

However, the authors warn that timing matters. Interventions are more effective before extensive neurodegeneration occurs — suggesting that prevention is far easier than reversal.

Practical Implications and Public Health Message

The researchers emphasize that exercise should be viewed as medicine — a form of “endogenous pharmacology.”

Unlike drugs, it is free, self-administered, and triggers the body’s natural mechanisms for repair and adaptation.

Still, more work is needed to define precise “dosage” recommendations:

- What is the ideal intensity and duration?

- How often should one train to optimize cognitive benefits?

- Which type of exercise (aerobic, resistance, or combined) has the greatest impact?

Until those questions are fully answered, the safest prescription is clear:

Move often, move with purpose, and keep moving for life.

A Hopeful Perspective on Aging

The take-home message from Erickson and colleagues is deeply optimistic:

Cognitive decline is not destiny.

Physical activity offers one of the most accessible, scalable, and scientifically proven ways to protect the brain.

By maintaining cardiovascular fitness and a physically active lifestyle, we can extend not just our lifespan, but our “healthspan” — the years of life lived with full mental and physical capacity.

Reference

Erickson, K. I., Donofry, S. D., Sewell, K. R., Brown, B. M., & Stillman, C. M. (2022). Cognitive Aging and the Promise of Physical Activity. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 18, 417–442. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-072720-014213

Forge Your Mind. Build Your Biology.

Join the Forge Biology newsletter — where science meets strength.

Every week, you’ll get:

-

Evidence-based insights on training, performance, and recovery

-

Real analyses of supplements that work (and the ones that don’t)

-

Deep dives into hormones, nutrition, and human optimization

No fluff. No marketing hype. Just data-driven knowledge to build a stronger body — and a sharper mind.

Subscribe now and start mastering your biology.