Introduction

Weightlifting is one of the most effective and time-tested methods to transform the body, improve physical performance, and strengthen the mind. Yet, many people approach the gym without a clear plan — doing whatever feels right that day, copying routines from others, or following random online trends. The result? Slow progress, lack of motivation, and sometimes injury. Preparing a workout properly means building a system that guides you toward measurable improvement.

A well-structured weightlifting routine isn’t about lifting the heaviest weights possible. It’s about creating consistent, progressive stress that your body adapts to over time. Strength, hypertrophy, endurance, or fat loss — each of these goals requires specific strategies regarding exercise selection, order, volume, and rest. When combined intelligently, they transform your training from chaos into controlled evolution.

Understanding the science behind workout preparation also helps you break plateaus. Instead of guessing what went wrong, you can analyze and adjust variables — intensity, rest, frequency, and technique. This analytical mindset separates those who “go to the gym” from those who truly train. Training means purpose, structure, and feedback.

Moreover, a planned program respects recovery, a factor often neglected by beginners. Muscles don’t grow while you lift weights — they grow while you rest. Proper scheduling allows your body to rebuild stronger fibers, reinforce tendons, and enhance neural coordination. Ignoring this balance leads to burnout or overtraining.

Finally, preparing a weightlifting workout is about creating a habit — a lifestyle anchored in discipline and clarity. Once your training has structure, you’ll not only perform better but also experience a deeper connection to your own potential. That’s the real reward of mastering this process.

Before continuing, I strongly suggest you read this post:

Choosing Objectives

Every effective workout begins with a goal. Without a clear destination, no training program can deliver meaningful results. Goals act as your compass — they determine how often you train, how many sets you perform, what exercises you select, and even how you eat and recover. The first mistake many people make is starting without truly defining what they want.

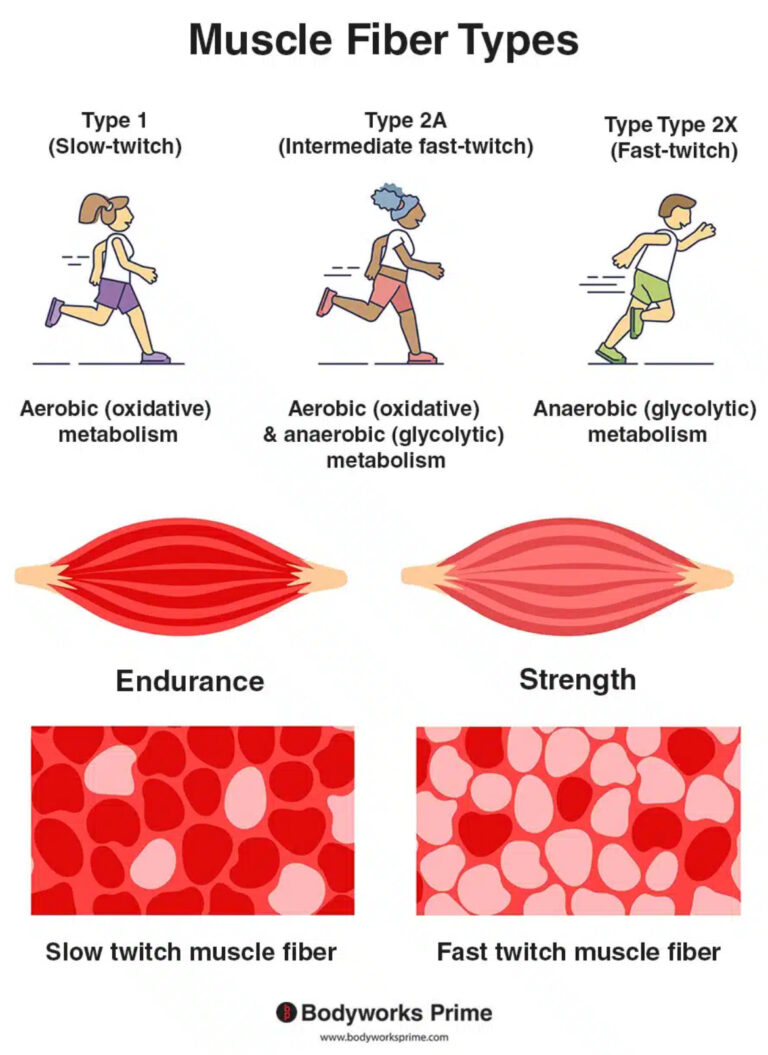

Let’s break this down into common objectives. If your goal is hypertrophy (muscle growth), the focus should be on creating mechanical tension and metabolic stress through moderate loads, controlled tempo, and sufficient volume. Typically, that means 8–12 repetitions per set with 60–90 seconds of rest. The aim is not just to move weight, but to create enough fatigue within the target muscle to stimulate adaptation.

If your goal is strength, you’ll train with heavier loads and lower repetitions. Strength training emphasizes neural efficiency — your body’s ability to recruit muscle fibers effectively. Here, the goal isn’t to feel “the burn” but to develop raw power and improve your 1RM (one-repetition maximum). Rest periods should be longer, from 2 to 5 minutes, allowing full recovery of your nervous system between sets.

For those focusing on endurance or fat loss, the strategy shifts again. Lighter loads, higher repetitions, and shorter rest periods increase the cardiovascular and metabolic demands of training. You’ll sweat more, breathe harder, and burn more calories — though the trade-off is that strength gains will be slower.

Once you define your main goal, stick to it for at least 6–8 weeks before making major changes. Constantly switching objectives prevents your body from fully adapting. Consistency is the secret ingredient behind every impressive physique or performance transformation.

Free Weights or Machines

There’s an endless debate about whether free weights or machines are superior — but the truth is, both are valuable tools depending on your context. Free weights, like barbells and dumbbells, demand coordination and stabilization. They engage not only your primary movers but also smaller stabilizing muscles that maintain control and balance. For example, a barbell squat activates the entire posterior chain — glutes, hamstrings, lower back — while also challenging your core to stabilize your spine.

Machines, however, provide controlled, guided movement. They reduce the risk of poor form and allow you to isolate specific muscles safely. This makes them excellent for beginners, people rehabbing injuries, or athletes looking to target weak points without overloading joints. The consistent resistance profile of a machine also allows for higher training volume with less fatigue on the nervous system.

One of the greatest advantages of free weights is functional carryover — the strength and stability you gain transfer to real-world activities and athletic performance. They also allow for micro-adjustments in grip, angle, and posture, providing a more natural movement pattern. In contrast, machines limit those variables, which can be both good (for safety) and bad (for flexibility).

A smart program uses both modalities strategically. For example, you might start with a compound movement using free weights (like bench press), then move to a machine (like a pec deck) to safely reach muscle failure without risk. This combination ensures maximum muscle activation and longevity in training.

Ultimately, the choice isn’t between free weights or machines — it’s about understanding when and why to use each. The best athletes and coaches know how to combine them intelligently based on training goals and experience level.

Exercise Order

The order of exercises in a workout significantly impacts both performance and results. Generally, the rule of thumb is to perform multi-joint (compound) movements before single-joint (isolation) exercises. This structure ensures that your larger, more demanding lifts are done while your energy and coordination are at their peak.

Starting with compound movements — like squats, deadlifts, bench presses, or pull-ups — allows you to stimulate multiple muscle groups simultaneously, building overall strength and efficiency. Because these exercises require maximum effort and technique, doing them early reduces the risk of poor execution due to fatigue.

After compound exercises, you move to isolation work — movements like bicep curls, triceps pushdowns, or lateral raises. These target specific muscles and can be pushed close to failure without major risk. They’re also excellent for correcting muscular imbalances or adding volume to lagging body parts.

There are exceptions, of course. Advanced athletes sometimes reverse the order intentionally through pre-exhaustion — performing isolation exercises first to fatigue a muscle before engaging it in a compound lift. This technique increases intensity and changes the stimulus.

Another important factor is how you alternate muscle groups. Pairing antagonistic muscles (like chest and back, or biceps and triceps) can improve efficiency and blood flow. This approach, called supersetting, saves time and enhances pump without sacrificing performance.

A logical exercise order protects your joints, maximizes strength output, and keeps your training organized. Think of it as a blueprint for consistent performance rather than random effort.

Number of Repetitions and Sets

Repetitions and sets are the building blocks of your training volume — the total amount of work performed. They determine how much mechanical stress you place on your muscles and, consequently, how they adapt. Getting this balance right is essential to progressing effectively without overtraining.

A repetition (rep) represents one complete movement cycle of an exercise. A set is a group of consecutive repetitions. For example, performing 10 squats, resting, then repeating that sequence two more times equals three sets of ten reps. Simple in theory, but powerful in practice.

Different goals require different rep ranges. Lower reps (1–6) with heavy weight target strength by increasing neural efficiency. Moderate reps (8–12) with controlled weight and tempo are ideal for hypertrophy, as they balance mechanical tension and metabolic fatigue. High reps (15–25) with lighter loads improve endurance and muscular stamina.

The total number of sets per exercise depends on your training frequency and experience. Beginners might do 2–3 sets per movement, while advanced lifters often perform 4–6 sets. Remember: more isn’t always better. Excessive volume without recovery leads to diminishing returns.

Finally, the concept of progressive overload ties everything together. Gradually increasing the number of reps, sets, or weight over time signals your body to grow stronger. Consistency, not perfection, creates results.

But wait… Maybe you should consider reading this post:

Intensity — What Is an RM?

Intensity refers to how hard you’re working relative to your maximum capacity. The most common way to measure it in weight training is by using Repetition Maximum (RM) — the heaviest load you can lift for a given number of repetitions before failure. Your 1RM is your maximum effort for one repetition. Your 10RM is the maximum for ten reps.

Understanding your RM helps you train precisely. For example, if your 1RM on the bench press is 100 kg, then 80% of that (80 kg) represents roughly your 8RM — the weight you can lift eight times with good form before failure. By using RM percentages, you can structure your workouts around specific intensities for strength, hypertrophy, or endurance.

Training too light fails to stimulate growth. Training too heavy too often leads to fatigue or injury. That’s why alternating intensity levels throughout the week — a method called periodization — is crucial. It allows recovery while still pushing adaptation.

Another practical concept is Rate of Perceived Exertion (RPE). Instead of relying solely on percentages, RPE measures effort on a scale from 1 to 10. For instance, an RPE of 9 means you could probably do one more rep before failure. Using RPE helps adjust for daily fluctuations in energy, stress, and sleep.

Ultimately, intensity is the driver of progress. Without it, even the best-designed program becomes a routine of maintenance rather than growth.

Types of Division (Workout Splits)

A workout split organizes your week by distributing muscle groups or movement patterns across different days. The right split balances frequency (how often you hit each muscle), volume (total weekly work), and recovery (time to adapt). Below you’ll find the 11 most common split structures—from minimalist 2-day schedules to high-frequency 8-day cycles—so you can match your time, training age, and goals.

1) 2-Day Split

What it is. Two weekly sessions. Variations include Full Body A/B, Upper/Lower, or Push/Pull.

Who it’s for. Busy lifters, beginners, or maintenance phases.

Sample (Full Body A/B):

- Mon: Full Body A • Thu: Full Body B

Pros. Time-efficient; easy recovery; great for learning movement patterns.

Cons. Limited weekly volume; sessions can run longer to cover all muscles.

Pro tips. Keep moves compound-heavy (squat/hinge/push/pull/carry), rotate accessory work every 4–6 weeks, and track loads meticulously to ensure progressive overload with the lower frequency.

2) 3-Day Split

What it is. Three sessions per week. Popular versions: Full Body, Upper/Lower/Full, and especially PPL (Push/Pull/Legs).

Who it’s for. Beginners and intermediates wanting balanced progress with solid recovery.

Sample (PPL):

- Mon: Push • Wed: Pull • Fri: Legs (Alternate A/B variations weekly)

Pros. Excellent balance of stimulus and rest; easy to sustain.

Cons. Less total volume than high-frequency plans; sessions may be longer.

Pro tips. Use A/B templates (Push A/B, Pull A/B, Legs A/B) to vary angles and grips, and wave intensity weekly (e.g., wk1 moderate, wk2 heavy, wk3 higher-rep).

3) 4-Day Split

What it is. Four sessions weekly; most popular is Upper/Lower run as A/B.

Who it’s for. Intermediates who want more volume without wrecking recovery.

Sample (UL A/B):

- Mon: Upper A • Tue: Lower A • Thu: Upper B • Fri: Lower B

Pros. Great weekly volume; simple structure; easy to periodize.

Cons. Requires consistent attendance; risk of overdoing accessories.

Pro tips. Anchor days with one main lift (bench, squat, hinge, overhead) then 3–5 accessories. Keep lower days from ballooning—quality over sheer exercise count.

4) 5-Day Split

What it is. Five training days; common template is PPL + Upper + Lower.

Who it’s for. Intermediates/advanced chasing hypertrophy and strength.

Sample (PPL + UL):

- Mon: Push • Tue: Pull • Wed: Legs • Fri: Upper • Sat: Lower (Thu/Sun rest)

Pros. High weekly stimulus; room for specialization; solid frequency.

Cons. Time-intensive; recovery must be managed tightly.

Pro tips. Treat Fri/Sat as “performance” days—keep them crisp. Use a light/medium/heavy wave across the week and cap sessions at ~70–80 minutes.

5) 6-Day Split

What it is. Six sessions; most popular is PPL run twice (A/B).

Who it’s for. Advanced lifters who tolerate high volume and want fast progress.

Sample (PPL A/B):

- Mon: Push A • Tue: Pull A • Wed: Legs A • Thu: Push B • Fri: Pull B • Sat: Legs B • Sun: Rest

Pros. Each muscle hits twice weekly; superb for hypertrophy when recovery is on point.

Cons. Thin margin for error—sleep, calories, and stress must align.

Pro tips. Split heavy compounds (A) and higher-rep/metabolic work (B). Deload every 4–6 weeks or run a “low-volume” week after two hard mesocycles.

6) 7-Day Split

What it is. Daily training; classic bro split with one major muscle per day (plus a recovery/abs/accessory day).

Who it’s for. Advanced hypertrophy focus; bodybuilders who love isolation volume.

Sample (Bro):

- Mon: Chest • Tue: Back • Wed: Shoulders • Thu: Arms • Fri: Legs • Sat: Core/Calves/Rear-delts • Sun: Active recovery

Pros. High specialization; deep mind–muscle work; easy to bias weak parts.

Cons. Minimal full-body carryover; higher overuse risk; life-schedule sensitive.

Pro tips. Rotate “emphasis blocks” (e.g., 4–6 weeks chest/back focus) and keep an active-recovery day truly restorative.

7) 8-Day Split (Extended Cycle)

What it is. An 8-day training loop (not tied to a 7-day week), often PPL + Arms/Weak Points with built-in rest after every four sessions.

Who it’s for. Advanced lifters wanting high frequency and smarter recovery spacing.

Sample (10-day cycle example):

- D1 Push A • D2 Pull A • D3 Legs A • D4 Arms/Weak A • D5 Rest • D6 Push B • D7 Pull B • D8 Legs B • D9 Arms/Weak B • D10 Rest → repeat

Pros. More recovery than a 7-day high-freq plan; great for weak-point work.

Cons. Off-calendar schedule complicates planning; still high total workload.

Pro tips. Track with a rolling template (not Monday–Sunday). Use “arms/weak” days for calves/rear delts/rotator cuff, not just biceps/triceps.

8) Push / Pull / Legs (PPL)

What it is. Organizes by movement pattern: push (chest/shoulders/triceps), pull (back/biceps), legs (quads/hamstrings/glutes/calves). Works in 3, 4, 5, or 6-day versions.

Why it’s popular. Even stimulus, clear structure, easy to scale from 3→6 days.

Watch-outs. The 6-day version is demanding—prioritize sleep, calories, and deloads.

Pro tips. Use A/B days to vary angles (horizontal/vertical pushes, hip hinge/knee-dominant), and track total weekly sets per muscle (10–20 per week for most).

9) Full-Body

What it is. Each session hits all major muscle groups (2–5 days/week).

Who it’s for. Beginners, busy professionals, or anyone prioritizing efficiency and balanced development.

Pros. High frequency per pattern; great motor learning; big ROI per session.

Cons. Less specialization; sessions can run long if you chase too many accessories.

Pro tips. Cap at 1–2 compounds per pattern per day; rotate lifts (e.g., squat Mon, hinge Wed, lunge Fri) to keep joints fresh.

10) Upper / Lower

What it is. Alternates upper-body and lower-body days (2, 4, or 6 sessions/week).

Why it’s loved. Simple, scalable, and works from novice to advanced.

Pros. Easy to program main lifts and accessories; solid recovery rhythm.

Cons. Can become long if you pack too much work into one side of the body.

Pro tips. Make Upper A heavy horizontal push/pull; Upper B vertical push/pull. Lower A squat-dominant; Lower B hinge-dominant.

11) Bro Split

What it is. One or two muscles per day (4–6 days/week) for hypertrophy.

Who it’s for. Aesthetics-driven trainees who respond well to high local volume.

Pros. Laser-focused pump and isolation; simple daily objective.

Cons. Each muscle is usually hit once/week—less ideal for strength or athletic carryover.

Pro tips. Add a light second touch for lagging parts (e.g., rear delts or calves) 48–72h later, and periodize intensity (heavy–moderate–high-rep blocks).

How to Choose Your Split (Quick Framework)

- Training age: Beginners → Full Body or Upper/Lower; Intermediates → Upper/Lower or PPL; Advanced → 5–6-day PPL, Bro, or 8-day loops.

- Time available: 2–3 days → Full Body; 4 days → Upper/Lower; 5–6 days → PPL or PPL+UL.

- Goal: Strength → higher frequency of main lifts; Hypertrophy → more weekly sets and angles; General fitness → balanced patterns.

- Recovery: If sleep/nutrition/stress are shaky, choose fewer days and nail consistency.

- Preference: The best split is the one you’ll actually run for 8–12 weeks.

Ready-to-Use Weekly Schedules (Copy/Paste)

6-Day PPL A/B: Mon Push A • Tue Pull A • Wed Legs A • Thu Push B • Fri Pull B • Sat Legs B

3-Day PPL: Mon Push • Wed Pull • Fri Legs

4-Day UL A/B: Mon Upper A • Tue Lower A • Thu Upper B • Fri Lower B

5-Day (PPL + UL): Mon Push • Tue Pull • Wed Legs • Fri Upper • Sat Lower

Examples of Workouts

Let’s look at how all these principles come together.

Example 1: Full-Body Routine (Beginner)

- Squat – 3×10

- Bench Press – 3×10

- Barbell Row – 3×10

- Dumbbell Shoulder Press – 3×12

- Plank – 3×30 seconds

This simple plan hits all major muscle groups while teaching core movement patterns. It’s efficient, easy to track, and builds foundational strength.

Example 2: ABC Split (Intermediate)

- Day A – Chest & Triceps: Bench Press, Incline Dumbbell Press, Cable Fly, Dips, Triceps Extension.

- Day B – Back & Biceps: Deadlift, Pull-Up, Seated Row, Barbell Curl, Hammer Curl.

- Day C – Legs & Shoulders: Squat, Leg Press, Romanian Deadlift, Lateral Raise, Shoulder Press.

This structure balances intensity and volume, allowing recovery between related muscle groups.

Example 3: ABCD Split (Advanced)

- A: Chest

- B: Back

- C: Legs

- D: Arms & Shoulders

Advanced lifters may use this to push specific muscles harder with advanced intensity techniques and higher total workload.

No matter the split, track your lifts, note progress, and adjust weekly. Every great program evolves — your body will tell you when to move forward.

Strategies for Increasing Intensity

Progress eventually stalls if the stimulus never changes. These techniques let you drive new adaptation without randomly “going harder.” Use them intentionally, rotate them, and monitor recovery.

A) Load- and Strength-Focused Methods

1) Cluster Sets

What: Break one heavy set into mini-sets with short intra-set rests.

How: 4–6 reps at ~85–92% 1RM, but done as singles/doubles with 10–20s between reps; 3–5 clusters.

When: Strength emphasis for compounds (squat, bench, deadlift, press).

Pitfalls: Easy to let total volume explode; cap clusters and rest strictly.

2) Wave Loading

What: Undulating heavy triples/doubles across “waves.”

How: Example 3/2/1 at 85/90/95%, rest 2–3 min, repeat wave slightly heavier.

When: Intermediate/advanced lifters chasing neural gains.

Pitfalls: Fatigue masks bar speed—stop if reps slow drastically.

3) Reverse Pyramid Training (RPT)

What: Heaviest set first, then reduce load 5–10% per back-off.

How: Top set 4–6 reps @ ~85–88% 1RM; 2–3 back-offs of 6–10 reps.

When: Limited time, want intensity + quality volume.

Pitfalls: Requires perfect warm-up ramp to avoid underperforming top set.

4) Accommodating Resistance (Bands/Chains)

What: Heavier at lockout, lighter at the bottom; matches strength curve.

How: 10–25% of total load from bands/chains on big lifts.

When: Sticking point work, speed-strength phases.

Pitfalls: Overbanding → form breakdown; learn setup.

5) Paused & Dead-Stop Reps

What: Eliminate stretch-reflex to increase force demand.

How: 1–2s pause at weakest point (squat hole, bench on chest).

When: Technique and bottom-end strength.

Pitfalls: Too long a pause tanks total volume; stay crisp.

B) Volume-Density Levers (More Work in Less Time)

6) EMOM (Every Minute on the Minute)

What: Timed sets start each minute.

How: 8–12 minutes of 2–5 quality reps on a main lift.

When: Power/technique maintenance with moderate fatigue.

Pitfalls: Choosing loads that force ugly reps—keep reps fast.

7) EDT (Escalating Density Training)

What: Do more total reps within a fixed time block.

How: Pair antagonists (e.g., rows + presses) for 10–15 minutes; beat rep PRs weekly.

When: Hypertrophy via density; great in accessory blocks.

Pitfalls: Form creep. Lock technique before chasing reps.

8) Rest-Shortening Cycles

What: Keep load/reps; cut rest 15–20s weekly.

How: 90s → 75s → 60s across a mesocycle.

When: Hypertrophy blocks to drive metabolite stress.

Pitfalls: Recovery debt—don’t pair with tons of failure work.

C) Set-Extending Techniques (Go Beyond Straight Sets)

9) Rest-Pause (classic)

What: Hit near-failure, rest 10–20s, continue.

How: 1 top set + 2–3 mini “bursts” (e.g., 12 reps, 20s, 5 reps, 20s, 3 reps).

When: Machines/isolation; safe failure.

Pitfalls: Not for risky compounds without spotter.

10) Myo-Reps

What: One activation set near failure, then short-rest micro-sets.

How: 15–20 to near-fail, then 3–5 reps every 10–15s for 3–6 rounds.

When: Pump + efficiency for accessories.

Pitfalls: Track total “effective reps” to avoid junk volume.

11) Drop Sets

What: Strip 10–25% weight immediately and continue.

How: 1–2 drops after failure.

When: Cables/machines; finishers.

Pitfalls: Too many drops = needless fatigue.

12) Mechanical Drop Sets

What: Make the exercise easier mechanically instead of lowering load.

How: Lateral raise → slight body English → partials; Chin-up wide → neutral → band-assisted.

When: Great for delts/backs/arms.

Pitfalls: Keep control—“cheat” should still target the muscle.

13) Forced Reps

What: Spotter assists past failure for 1–2 reps.

How: Only on stable setups (bench machine, hack squat).

When: Peak weeks, advanced lifters.

Pitfalls: Overuse nukes recovery; 1–2 assisted reps max.

D) Metabolic-Stress & Time-Under-Tension Tactics

14) Tempo Manipulation

What: Slow eccentrics, controlled pauses, explosive concentrics.

How: 3–0–1–0 or 4–1–1–0 tempos for 6–12 reps.

When: Hypertrophy, technique reinforcement.

Pitfalls: Load must drop—accept it.

15) Constant-Tension & Partials

What: Cut lockout or bottom to keep tension; finish with partials.

How: 40–60s sets for delts, quads, chest.

When: Target stubborn muscles.

Pitfalls: Joint comfort—don’t camp in painful mid-ranges.

16) Lengthened-Bias / Stretch-Mediated Work

What: Emphasize long-muscle-length positions (e.g., incline curls, RDLs).

How: Longer eccentrics, pauses in the stretch, 6–10 reps.

When: Big hypertrophy driver.

Pitfalls: Soreness spikes—introduce gradually.

17) Intra-Set Isometrics

What: Holds inside the set to amplify fatigue.

How: 5-sec hold mid-range each rep for 6–8 reps.

When: Delts, lats, pecs; mind–muscle connection.

Pitfalls: Don’t hold so long you lose position.

18) Blood-Flow Restriction (BFR)

What: Light loads with cuffs partially occluding venous return.

How: 30-15-15-15 reps @ ~20–30% 1RM, 30–45s rests.

When: Arms/quads; deloads or joint-friendly phases.

Pitfalls: Use proper cuffs/pressure; avoid if you have vascular/medical contraindications.

E) Pre-/Post-Fatigue & Pairings

19) Pre-Exhaust (isolation → compound)

How: Leg extension → squat; fly → bench.

When: Improve target muscle stimulus in compounds.

Pitfalls: Don’t pre-fatigue so hard that form collapses.

20) Post-Exhaust (compound → isolation)

How: Bench → cable fly; Row → pullover.

When: Extend work after quality heavy sets.

Pitfalls: Keep isolation strict; stop short of joint pain.

21) Antagonist Supersets

How: Push + pull (bench + row), flexor + extensor.

When: Density + pump, better joint balance.

Pitfalls: Don’t pair two grip-crushers if grip is limiting.

22) Giant Sets / Tri-Sets

How: 3–4 exercises back-to-back for same region.

When: Shoulders/arms/back detail.

Pitfalls: Exercise order matters—skill first, then pump.

F) Eccentric & Range-of-Motion Progressions

23) Eccentric Overload / Negatives

How: 3–5s lowers with assisted concentrics; 3–5 reps.

When: Advanced hypertrophy/strength phases.

Pitfalls: DOMS and recovery cost—use sparingly.

24) ROM Progression

What: Increase range over weeks.

How: Deficit pulls, deeper split squats, longer stretch positions.

When: Mobility + hypertrophy synergy.

Pitfalls: Don’t force range that compromises spinal/pelvic control.

G) Programming Levers (Intensity Without Tricks)

25) Double-Progression

What: Add reps within a range, then add load.

How: 8–12 reps; when you hit 12 across sets, add weight and restart.

When: Core driver for most exercises.

Pitfalls: Jumping load too aggressively → form drift.

26) Rep in Reserve (RIR) / RPE Autoregulation

What: Stop with 0–3 reps “left in the tank” depending on goal.

How: Strength work @ RPE 7–9; volume @ RPE 6–8.

When: Day-to-day fatigue management.

Pitfalls: Chronic “easy” efforts stall gains; calibrate honestly.

27) Set Caps & “Top-+-Back-Off” Model

What: One heavy top set, then 1–3 back-offs for volume.

How: Top 3–5 reps @ ~85–90%, back-offs 6–10 reps @ ~70–80%.

When: Keeps quality high while accumulating stimulus.

Pitfalls: Don’t chase hero top sets weekly—rotate rep targets.

H) Practical Plug-and-Play Examples

- Chest Hypertrophy Day (Post-Exhaust + Tempo):

Bench 4×6 (2–3 RIR) → Incline DB 3×8 (3-1-1 tempo) → Cable Fly 3×12 + 1 mechanical drop → Push-ups constant tension AMRAP. - Legs (Lengthened Bias + Rest-Pause):

Back Squat 5×5 → RDL 3×8 (3-sec ecc) → Leg Press 2×12 + rest-pause burst → Walking Lunges 2×16 steps → Seated Calf 3×12 (pause stretch). - Pull (Cluster + Antagonist Supersets):

Deadlift (cluster 6×2 @ 88–90%) → Superset: Chest-Supported Row 4×8 / Low-Incline DB Press 4×10 → Pulldown 3×10 + 1 drop → Face Pulls 3×15.

Usage Rules (to stay strong, not smashed)

Exercise choice matters. Reserve “to-failure” tactics for machines/cables and safer isolations; keep compounds mostly technical and shy of failure.

One high-stress method per muscle per session. Don’t stack rest-pause + drops + heavy eccentrics on the same movement.

Wave the stress. Hard technique this week? Go simpler next week (straight sets or back-off volume).

Deloads or low-volume weeks every 4–6 hard weeks.

Track performance + soreness + sleep. If bar speed and mood crater, pull back.

Killer Mindset

No workout plan will save you if your mind quits first. The right mindset separates champions from the crowd. Physical training is ultimately mental training — a daily battle between comfort and discipline. The body stops when the mind allows it.

The “killer mindset” is not about aggression; it’s about commitment. It’s the internal voice that says, one more rep, even when your muscles burn. It’s the refusal to skip the gym because you’re tired. It’s showing up, again and again, long after motivation fades.

Imagine this: if someone pointed a gun to your head and demanded one more rep — could you do it? Of course, you could. That means you had more in you all along. True intensity begins when you reach that edge — where comfort ends and growth begins.

This mindset also extends beyond the gym. How you train reflects how you live. The discipline, consistency, and resilience you build through lifting transfer to business, relationships, and every challenge life throws your way. Weightlifting becomes a metaphor for existence: resistance is the path to strength.

Ultimately, mindset isn’t about hype; it’s about honor — honoring your potential and your promises to yourself. Every rep is a declaration that you’re not settling for mediocrity.

Final Thoughts

Preparing a weightlifting workout is both art and science. It requires understanding physiology, but also mastering psychology. It’s about organizing variables — volume, intensity, rest — while never forgetting the soul of training: purpose.

No matter your goal, success in the gym depends on clarity, consistency, and courage. Clarity to define what you’re chasing, consistency to show up when it’s inconvenient, and courage to push when it hurts. These three elements transform physical effort into progress.

Remember: the perfect plan on paper means nothing if you don’t execute it with heart. Conversely, an imperfect plan done with total commitment will outperform the fanciest scientific routine. The secret isn’t in the spreadsheet — it’s in the sweat.

As you prepare your next workout, take a moment to plan, to visualize, and to commit. Make every set count. Build your body, but also your character. Because in the end, iron doesn’t just shape muscle — it forges the mind.

Forge Your Mind. Build Your Biology.

Join the Forge Biology newsletter — where science meets strength.

Every week, you’ll get:

-

Evidence-based insights on training, performance, and recovery

-

Real analyses of supplements that work (and the ones that don’t)

-

Deep dives into hormones, nutrition, and human optimization

No fluff. No marketing hype. Just data-driven knowledge to build a stronger body — and a sharper mind.

Subscribe now and start mastering your biology.