Running is one of the most instinctive and accessible forms of physical exercise — yet few people do it strategically. What separates a casual jogger from an athlete in constant evolution is not genetics or expensive gear, but structure. Organizing your running training means understanding the relationship between effort and recovery, and knowing when to push and when to rest. Without a plan, you might feel like you’re progressing, but often you’re just repeating the same effort week after week.

A well-designed running program respects the body’s need for adaptation. Just as you wouldn’t lift the same weight indefinitely in the gym, you shouldn’t run the same distance, pace, or intensity every time. The principles of sports science — overload, progression, specificity, and recovery — apply equally to running. When these are aligned with your goals, your body becomes a far more efficient machine for endurance, speed, and resilience.

Proper organization also protects you from one of the most common problems in running: injuries caused by imbalance. Too much intensity without rest leads to stress fractures, tendonitis, and burnout. Too little challenge leads to stagnation. Striking the right balance allows you to train smarter — not just harder.

In this guide, we’ll break down the essential elements of planning your running training: defining clear objectives, structuring your weekly schedule, applying periodization, managing intensity, and understanding how metrics can help you progress. The goal is not only to make you faster but also to make running sustainable for life.

Before start, I strongly recommend you also read:

1. Setting Your Objectives

Every effective training plan starts with a purpose. Running “to get fit” is not the same as training for a 10K, a marathon, or improving recovery from another sport. Without a clear objective, you cannot choose the right intensity, frequency, or recovery strategy. Your goal defines everything: how often you run, how fast you go, and even what kind of shoes you wear.

If your main goal is weight loss or general fitness, your focus should be on consistency and total weekly energy expenditure. You don’t need to sprint — instead, aim for longer runs at low intensity, complemented by proper nutrition and strength training to preserve lean mass. For beginners, three runs per week is enough to start building endurance safely.

Those training for performance and competition need a different approach. This involves progression in pace, structured intervals, and sessions designed to improve VO₂ max and lactate threshold — the point at which muscles start accumulating fatigue. A competitive runner’s plan typically includes alternating hard and easy days, ensuring adaptation while preventing overtraining.

If you’re pursuing endurance and stamina, such as for marathons or ultra runs, volume becomes your best friend. You’ll need to develop an aerobic base through long, slow runs that teach your body to efficiently use fat as fuel. These sessions are less glamorous but are the foundation for resilience over long distances.

Finally, those who seek speed and power — sprinters or hybrid athletes — will benefit from explosive work: short, high-intensity intervals, hill sprints, and plyometrics. These sessions train the neuromuscular system and improve stride mechanics, coordination, and running economy. The key takeaway is this: before organizing your training, know what success means to you. A plan without purpose is just movement.

2. Weekly Organization

A well-organized training week is like a balanced diet — each component plays a role. Too much of one and you burn out; too little and you underperform. Most runners benefit from dividing their week into specific run types that target endurance, strength, and recovery simultaneously. Think of it as your personal “ecosystem” of effort and rest.

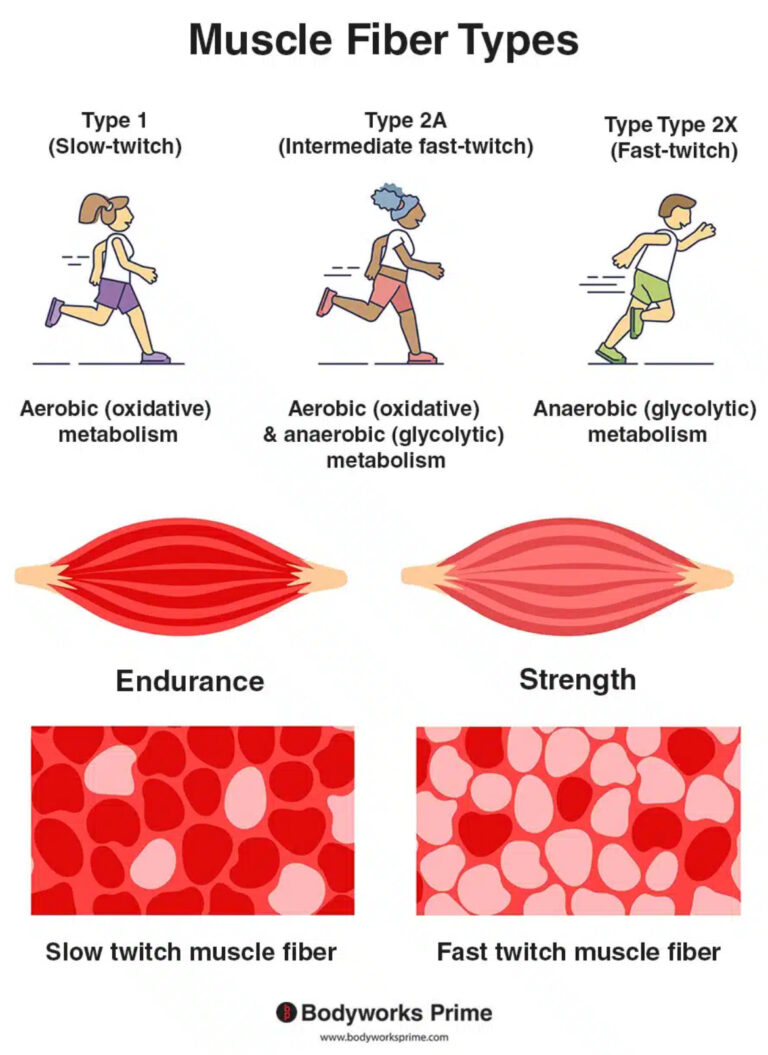

Long runs are the backbone of endurance training. They improve cardiovascular efficiency, increase glycogen storage, and teach mental toughness. These runs should be performed at an easy, conversational pace, typically 60–120 minutes depending on your level. They train your body to use oxygen and fat more efficiently — essential for any long-distance goal.

Speed sessions, on the other hand, target your body’s upper limits. Intervals of 400m to 1000m at near-maximal effort challenge your anaerobic capacity and increase your VO₂ max. These are demanding workouts and should only appear once a week for most runners. Always follow them with easier days to allow recovery.

Tempo runs sit between endurance and speed work. You run at a comfortably hard pace, usually for 20–40 minutes. The goal here is to raise your lactate threshold — the pace you can sustain for a longer period before fatigue sets in. Over time, this improves your race pace and overall running economy.

Lastly, you must include recovery runs, cross-training, and rest days. Easy runs at low intensity promote blood flow and tissue repair, while activities like swimming or cycling maintain cardiovascular fitness without impact stress. Rest days are not “off days” — they are when your body actually becomes stronger. Skipping rest is like trying to build a house without letting the foundation dry.

3. Periodization: The Bigger Picture

Periodization is the art and science of dividing training into distinct phases. Each phase develops specific qualities — endurance, power, speed — while preventing stagnation and injury. It’s what transforms random exercise into a system of continuous improvement. Without it, you risk doing “a lot” but achieving little.

The first stage, the Base Phase, focuses on aerobic conditioning and technique. Here, volume increases gradually, and intensity remains low. This phase typically lasts 4–8 weeks and builds the cardiovascular and muscular foundation for heavier training later on. It’s about patience, discipline, and consistency — not heroics.

Next comes the Build Phase, where you start introducing intervals, hills, and tempo runs. Your mileage may stabilize, but the intensity rises. The goal is to stimulate adaptation by challenging your heart, lungs, and muscles. This phase can feel demanding, so nutrition, sleep, and recovery practices become crucial.

The Peak Phase is when you fine-tune performance for competition or testing. You simulate race conditions and reduce total volume slightly, allowing your body to consolidate the gains. This is also when tapering begins — a strategic reduction of training load to ensure freshness and top performance on race day.

Finally, the Recovery or Transition Phase allows both body and mind to reset. Volume and intensity drop significantly for one to two weeks. This phase prevents overtraining and helps you prepare for the next training cycle. Skipping it often leads to chronic fatigue and injuries. Periodization is cyclical, not linear — after recovery, the process begins again, but at a higher level.

4. Intensity and Metrics

Running intensity is what turns your training from a random effort into targeted performance. Understanding how to measure and control intensity allows you to run smarter, not just harder. Today’s runners have access to a wealth of data, but numbers only matter if you know how to interpret them.

The most traditional and accessible tool is heart rate training. By using heart rate zones (based on your maximum heart rate), you can tailor each session to the desired energy system. Easy runs should stay in zones 1–2, where fat oxidation dominates. Tempo and threshold runs fall into zone 3, where your body learns to tolerate higher lactate levels. Intervals in zones 4–5 target anaerobic performance and sprint capacity.

Another approach is pace-based training, which relies on GPS watches or apps to track how fast you run per mile or kilometer. This method works well for flat terrain but can be misleading on hills or windy conditions. That’s where power-based training comes in — it measures the actual effort in watts, independent of terrain. This metric, though newer, gives remarkable precision and is increasingly popular among serious athletes.

For those who prefer simplicity, Rate of Perceived Exertion (RPE) remains one of the best tools. It requires no device — only awareness. On a scale from 1 to 10, you estimate how hard you feel you’re working. Over time, you’ll develop an internal calibration that’s surprisingly accurate. The best runners blend data with intuition — technology enhances awareness but never replaces it.

Tracking progress goes beyond raw data. Pay attention to how you feel: Are you sleeping well? Is your motivation stable? Are your legs heavy or light during warm-up? These subjective cues are just as vital as heart rate graphs. Metrics should serve you — not control you.

Training Zones Based on Heart Rate Percentage

Heart rate–based training is one of the most reliable ways to gauge and control exercise intensity. By tracking your heart rate as a percentage of your maximum heart rate (HRmax), you can tailor every run to target a specific physiological adaptation — from fat-burning and aerobic endurance to speed and anaerobic power. Understanding these zones allows you to train with precision rather than guesswork.

To determine your estimated maximum heart rate, a simple formula often used is:

HRmax = 220 − age.

While this gives a rough estimate, testing under supervision (such as a graded treadmill test) provides a more accurate value. Once you know your HRmax, each training zone can be defined as a percentage of it.

Zone 1: Active Recovery (50–60% HRmax)

This is your easiest effort level — a relaxed pace where conversation is effortless. Zone 1 promotes circulation, aids recovery, and develops the capillary network that delivers oxygen to your muscles. It’s ideal for warm-ups, cooldowns, and recovery runs.

Zone 2: Aerobic Base (60–70% HRmax)

Often called the fat-burning zone, Zone 2 is the foundation of endurance training. Running at this intensity enhances mitochondrial density and improves your ability to oxidize fat as a primary energy source. It’s sustainable for long durations and should make up the majority of mileage for endurance athletes.

Zone 3: Tempo / Aerobic Threshold (70–80% HRmax)

This is a comfortably hard effort — challenging, but not exhaustive. Training in Zone 3 raises your aerobic threshold, meaning you can maintain higher speeds without accumulating excessive lactate. It’s ideal for tempo runs and steady-state workouts.

Zone 4: Anaerobic Threshold (80–90% HRmax)

In this zone, your breathing becomes labored, and conversation is limited to short phrases. Zone 4 training improves lactate tolerance and boosts your ability to sustain high-intensity efforts. This is where interval training and hill repeats are typically performed.

Zone 5: Maximum Effort (90–100% HRmax)

This is your sprint zone — short bursts of near-maximal effort lasting seconds to a few minutes. It develops maximal oxygen uptake (VO₂ max) and neuromuscular efficiency. Zone 5 should be used sparingly due to its high stress on the body, followed by adequate recovery.

Summary Table

| Zone | Intensity | % HRmax | Main Benefit | Typical Session |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Very Easy | 50–60% | Active recovery | Easy jogs, cooldowns |

| 2 | Easy | 60–70% | Aerobic base, fat metabolism | Long runs |

| 3 | Moderate | 70–80% | Aerobic efficiency, tempo endurance | Tempo runs |

| 4 | Hard | 80–90% | Lactate threshold, power | Intervals, hill sprints |

| 5 | Maximal | 90–100% | VO₂ max, speed | Short sprints, maximal efforts |

By organizing your runs around heart rate zones, you ensure every session has a clear purpose. Training too hard every day leads to fatigue and stagnation, while balancing intensity — spending most of your time in Zones 1–2 and strategically adding higher-zone work — builds a strong, efficient, and resilient runner’s heart.

5. Final Considerations

At the heart of all effective training lies one golden principle: consistency beats intensity. You don’t need to destroy yourself every session. What matters most is showing up — week after week, month after month. Running rewards patience and punishes ego. The body evolves through steady, deliberate stress followed by recovery, not through recklessness.

Recovery is an active part of training, not its opposite. Sleep, nutrition, hydration, and mental balance are as important as your longest run. Protein repairs muscles, carbohydrates replenish glycogen, and fats support hormonal function. Neglect any of these, and your performance will plateau no matter how perfectly structured your workouts are.

Incorporate strength training twice per week. Exercises like squats, lunges, and deadlifts improve running economy and reduce the risk of knee, hip, and ankle injuries. Core stability, too, plays a critical role — a strong midsection ensures efficient energy transfer and reduces fatigue on long runs.

Finally, remember why you started running in the first place. For some, it’s fitness; for others, it’s therapy. Structure your training, but don’t lose the joy of movement. The perfect running program is one that you can sustain physically, mentally, and emotionally. Discipline creates progress, but passion keeps you moving forward.

In the end, running is not just about reaching a finish line — it’s about learning to manage effort, time, and self-mastery. Plan your training with intention, respect your body’s signals, and you’ll not only become a better runner but also a stronger, more resilient human being.

Forge Your Mind. Build Your Biology.

Join the Forge Biology newsletter — where science meets strength.

Every week, you’ll get:

-

Evidence-based insights on training, performance, and recovery

-

Real analyses of supplements that work (and the ones that don’t)

-

Deep dives into hormones, nutrition, and human optimization

No fluff. No marketing hype. Just data-driven knowledge to build a stronger body — and a sharper mind.

Subscribe now and start mastering your biology.