The Rise of Biohacking: Science for Everyone

For much of modern history, biology and medicine have remained behind institutional walls — accessible only to those with laboratory access or advanced degrees. But the biohacking movement, rooted in the philosophy of “citizen science,” has changed that landscape.

Biohacking blends self-experimentation, open-source biotechnology, and personalized data tracking to empower individuals to take charge of their biology. It emerged from the DIYbio culture — a global network of independent laboratories and innovators seeking to democratize science (Delfanti, 2013). This movement promotes the idea that biological knowledge should be accessible, modifiable, and open to everyone.

Today, biohacking encompasses much more than synthetic biology. It includes optimizing sleep, nutrition, cognition, hormonal balance, and longevity through measurable interventions — often assisted by wearable technology, genetic testing, and nutritional science (Hurlbut, Tirosh-Samuelson, & Chandler, 2020).

For women, biohacking is not merely about performance. It is a movement toward autonomy and biological literacy in a system that has historically ignored or misunderstood female physiology.

When Biology Becomes Personal

Medical research has long prioritized male physiology as the default model for human health, a bias that has led to significant gaps in understanding female biology (Holdcroft, 2007). Symptoms of cardiovascular disease, for instance, often present differently in women, yet diagnostic standards have been based on male data (Regitz-Zagrosek & Kararigas, 2017). Hormonal cycles, metabolic variations, and the influence of estrogen and progesterone on neurotransmitters have also been overlooked.

Biohacking redefines this imbalance by giving women access to self-tracking tools and biological literacy. Through continuous glucose monitors (CGMs), sleep trackers, heart rate variability (HRV) sensors, and hormone tests, women can now quantify how their bodies respond to nutrition, exercise, and stress.

Such data empowers women to adapt their lifestyles with precision. For example, blood sugar monitoring helps identify insulin resistance — a precursor to metabolic syndrome and PCOS — long before clinical diagnosis (Dunaif, 1997). Similarly, tracking HRV can reveal early signs of overtraining or chronic stress, both of which disproportionately affect women due to hormonal fluctuations (Schmalenberger et al., 2019).

This is the new frontier of personalized health — one where biology becomes personal, measurable, and actionable.

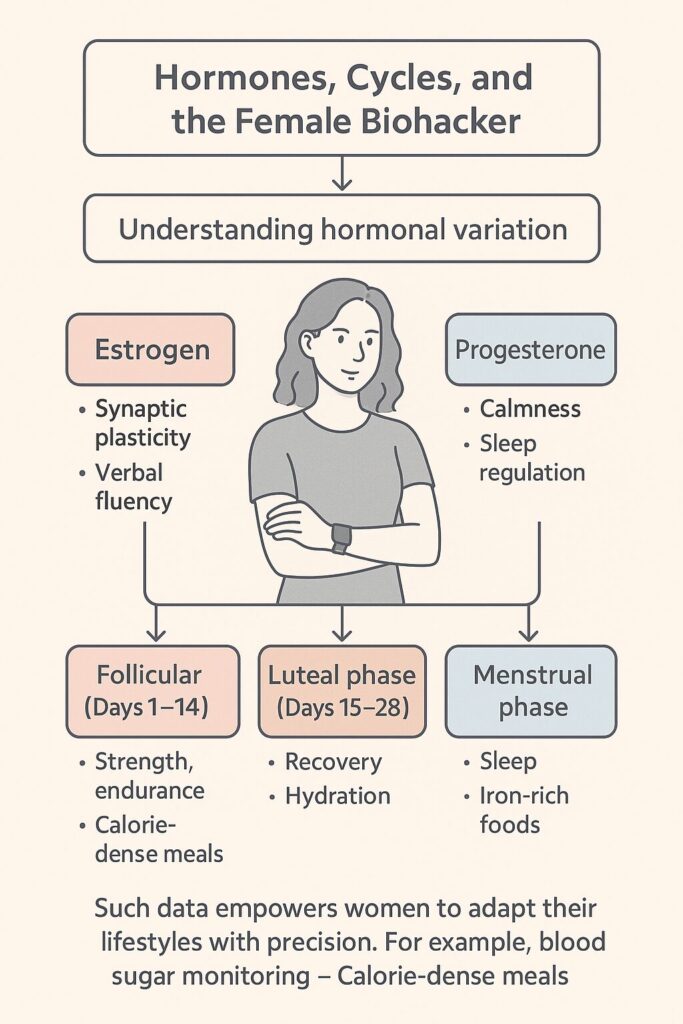

Hormones, Cycles, and the Female Biohacker

Understanding hormonal variation is central to women’s biohacking. The menstrual cycle is not merely a reproductive rhythm but a dynamic endocrine orchestra that influences mood, metabolism, cognition, and physical performance (Sundström-Poromaa & Gingnell, 2014).

Female biohackers are increasingly leveraging this knowledge to optimize their routines. Evidence shows that estrogen enhances synaptic plasticity and verbal fluency, while progesterone promotes calmness and sleep regulation (Toffoletto, Lanzenberger, Gingnell, Sundström-Poromaa, & Comasco, 2014).

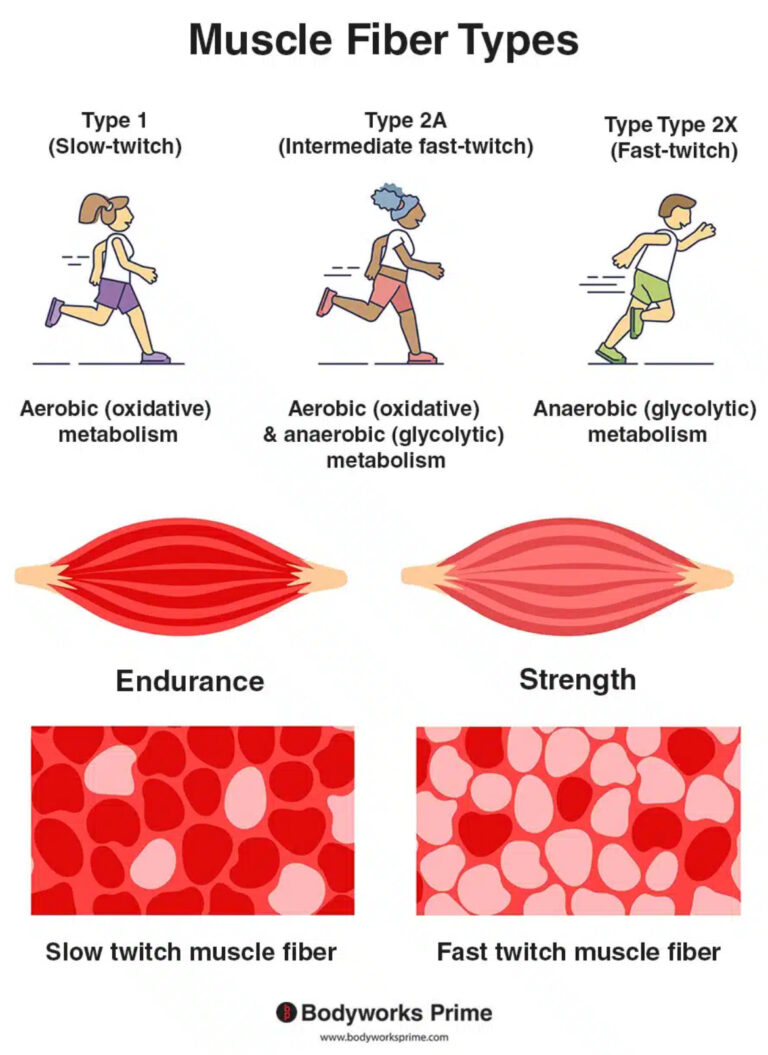

By aligning training, nutrition, and productivity with hormonal phases, women can improve results and reduce burnout. For instance:

- Follicular phase (Days 1–14): Higher estrogen supports strength, endurance, and motivation. Resistance training and calorie-dense meals with adequate carbohydrates are beneficial (Sung et al., 2014).

- Luteal phase (Days 15–28): Progesterone increases basal body temperature and may reduce exercise tolerance. Prioritizing recovery, magnesium intake, and hydration is key (Tenan, Brothers, Tweedell, Hackney, & Griffin, 2016).

- Menstrual phase: Inflammatory markers rise; focusing on sleep, iron-rich foods, and light movement may enhance well-being (Ongaro & Barnes, 2022).

These cycle-based strategies are supported by wearable technology capable of detecting subtle physiological changes, from skin temperature to oxygen saturation. What was once invisible — hormone-driven variation in performance and mood — can now be tracked, analyzed, and optimized.

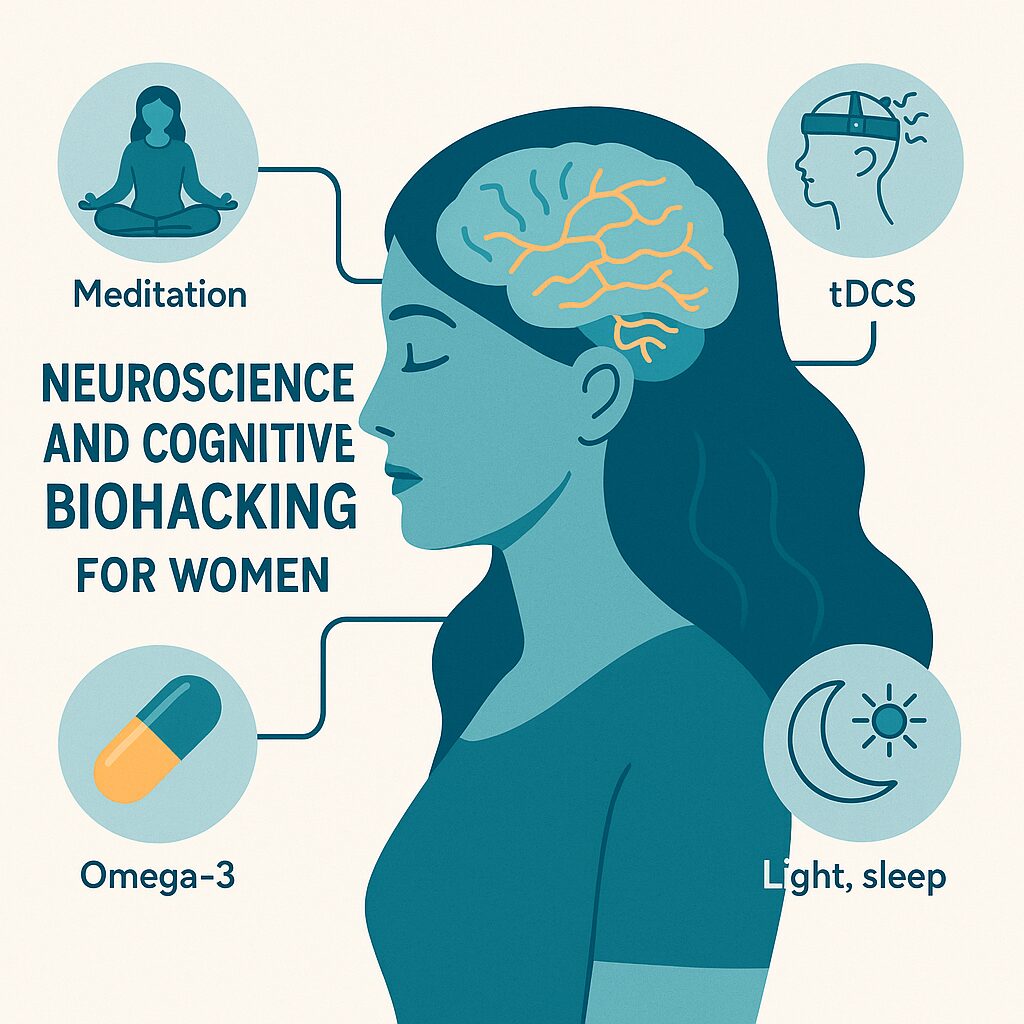

Neuroscience and Cognitive Biohacking for Women

Beyond hormones, the female brain exhibits unique responses to neurotransmitters such as dopamine and serotonin, affecting stress resilience, motivation, and mood. Fluctuations in estrogen levels directly influence these systems, making cognitive performance cyclical as well (Dubol et al., 2021).

Interventions like meditation, omega-3 supplementation, and transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) — a tool once exclusive to research labs — have been adapted by biohackers for mood stabilization and neuroplasticity (Nitsche et al., 2008).

Women’s cognitive biohacking, however, also involves reclaiming focus and productivity in a world designed for male circadian patterns. Chronobiological research has shown that women tend to have earlier circadian phases and greater vulnerability to sleep disruption (Duffy et al., 2011). Adjusting light exposure, caffeine timing, and sleep-wake cycles can therefore significantly enhance mental clarity and emotional regulation.

Ethics, Safety, and the Feminine Dimension of Biohacking

While biohacking empowers self-knowledge, it also challenges ethical boundaries. The European DIYbio Code of Ethics (2011) stresses transparency, safety, and respect for all living systems. Yet, as feminist scholars have noted, the biohacking movement initially reflected a masculine ethos — focused on competition, control, and “self-made” experimentation (Jen, 2015).

The emerging wave of female biohackers introduces a paradigm shift: collaboration, empathy, and sustainability. Rather than pursuing dominance over biology, women often approach biohacking as cooperation with biology — optimizing within natural rhythms instead of overriding them.

This integrative model aligns with contemporary systems biology, which views the body as an adaptive network rather than a mechanical structure (Kitano, 2002). The feminine approach to biohacking thus becomes not only a scientific evolution but also a philosophical one — merging data-driven insights with intuition, community, and holistic care.

Global Perspectives: From Silicon Valley to the Global South

In affluent nations, biohacking is often marketed as an elite performance trend — wearable sensors, nootropics, and longevity diets. But in the Global South, biohacking takes on a different meaning: accessibility, survival, and innovation under constraint.

Projects such as the Oxytocin Diagnostic Toolkit, developed by the Denver Biolabs team, exemplify how open-source biology can address maternal health crises by creating low-cost devices to detect postpartum hemorrhage (Meyer, 2020). Similarly, the Open Biomedical Initiative designs affordable prosthetics and incubators for underserved regions.

In this context, biohacking is not vanity science — it’s humanitarian biotechnology. For many women, it represents the ability to monitor health, prevent disease, and protect life in places where medical infrastructure is limited.

Empowerment Through Knowledge

To biohack as a woman is to reclaim authorship over your body. It is not a rejection of medicine, but an expansion of it — one that acknowledges complexity, individuality, and agency.

As women continue to integrate scientific literacy, wearable data, and open innovation into their daily lives, they are also rewriting what health means in the 21st century: not compliance, but participation; not dependency, but understanding.

Ultimately, biohacking isn’t about perfection — it’s about liberation through knowledge.

References

Bagnolini, C. (2018). Feminist perspectives on biohacking: Gender and ethics in DIY biology. BioSocieties, 13(3), 435–448.

Delfanti, A. (2013). Biohackers: The politics of open science. Pluto Press.

Dubol, M., Epperson, C. N., Sacher, J., Pletzer, B., Derntl, B., Lanzenberger, R., Sundström-Poromaa, I., & Comasco, E. (2021). Neuroimaging the menstrual cycle: A multimodal systematic review. Frontiers in Neuroendocrinology, 60, 100878.

Duffy, J. F., Cain, S. W., Chang, A. M., Phillips, A. J. K., Münch, M. Y., Gronfier, C., Wyatt, J. K., Dijk, D. J., Wright, K. P., & Czeisler, C. A. (2011). Sex difference in the near-24-hour intrinsic period of the human circadian timing system. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 108(Suppl 3), 15602–15608.

Dunaif, A. (1997). Insulin resistance and the polycystic ovary syndrome: Mechanism and implications for pathogenesis. Endocrine Reviews, 18(6), 774–800.

Hurlbut, J. B., Tirosh-Samuelson, H., & Chandler, J. A. (2020). Perfecting human futures: Transhumanism and biohacking. Springer.

Jen, S. (2015). Gender and the hacker ethos: The masculine coding of innovation. Social Studies of Science, 45(6), 906–928.

Kitano, H. (2002). Systems biology: A brief overview. Science, 295(5560), 1662–1664.

Meyer, M. (2020). Biohacking and DIY science: An ethnography of making biology personal. Polity Press.

Nitsche, M. A., Cohen, L. G., Wassermann, E. M., Priori, A., Lang, N., Antal, A., Paulus, W., Hummel, F., Boggio, P. S., Fregni, F., & Pascual-Leone, A. (2008). Transcranial direct current stimulation: State of the art 2008. Brain Stimulation, 1(3), 206–223.

Ongaro, G., & Barnes, C. (2022). Exercise and the menstrual cycle: Hormonal regulation, inflammation, and recovery. Journal of Women’s Health, 31(2), 234–245.

Regitz-Zagrosek, V., & Kararigas, G. (2017). Mechanistic pathways of sex differences in cardiovascular disease. Physiological Reviews, 97(1), 1–37.

Schmalenberger, K. M., Eisenlohr-Moul, T. A., Jarczok, M. N., Eckstein, M., Schneider, E., Brenner, I. G., Kiesner, J., & Ditzen, B. (2019). Menstrual cycle changes in vagally-mediated heart rate variability are associated with progesterone: Evidence from two within-person studies. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 8(2), 163.

Sung, E., Han, A., Hinrichs, T., Vorgerd, M., Manchado, C., & Platen, P. (2014). Effects of follicular versus luteal phase-based strength training in young women. International Journal of Sports Medicine, 35(09), 684–689.

Sundström-Poromaa, I., & Gingnell, M. (2014). Menstrual cycle influence on cognitive function and emotion processing — from a reproductive perspective. Frontiers in Neuroscience, 8, 380.

Tenan, M. S., Brothers, R. M., Tweedell, A. J., Hackney, A. C., & Griffin, L. (2016). Changes in resting heart rate variability across the menstrual cycle. Psychophysiology, 53(3), 446–454.

Toffoletto, S., Lanzenberger, R., Gingnell, M., Sundström-Poromaa, I., & Comasco, E. (2014). Emotional and cognitive functional imaging of estrogen and progesterone effects in the female human brain: A systematic review. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 50, 28–52.

Forge Your Mind. Build Your Biology.

Join the Forge Biology newsletter — where science meets strength.

Every week, you’ll get:

-

Evidence-based insights on training, performance, and recovery

-

Real analyses of supplements that work (and the ones that don’t)

-

Deep dives into hormones, nutrition, and human optimization

No fluff. No marketing hype. Just data-driven knowledge to build a stronger body — and a sharper mind.

Subscribe now and start mastering your biology.