Preparing Your Workout 1.01 – Forge Biology Series

Stepping into a gym for the first time can feel overwhelming. Rows of unfamiliar machines, people lifting heavy weights, and the constant rhythm of movement can easily intimidate beginners. Yet, science shows that the simple act of strength training — when structured correctly — can dramatically improve body composition, metabolic health, mood, and even longevity (Westcott, 2012; Schoenfeld et al., 2019). This guide will help you understand how to prepare your workouts intelligently, no matter your goal.

What Is Weight Training, Really?

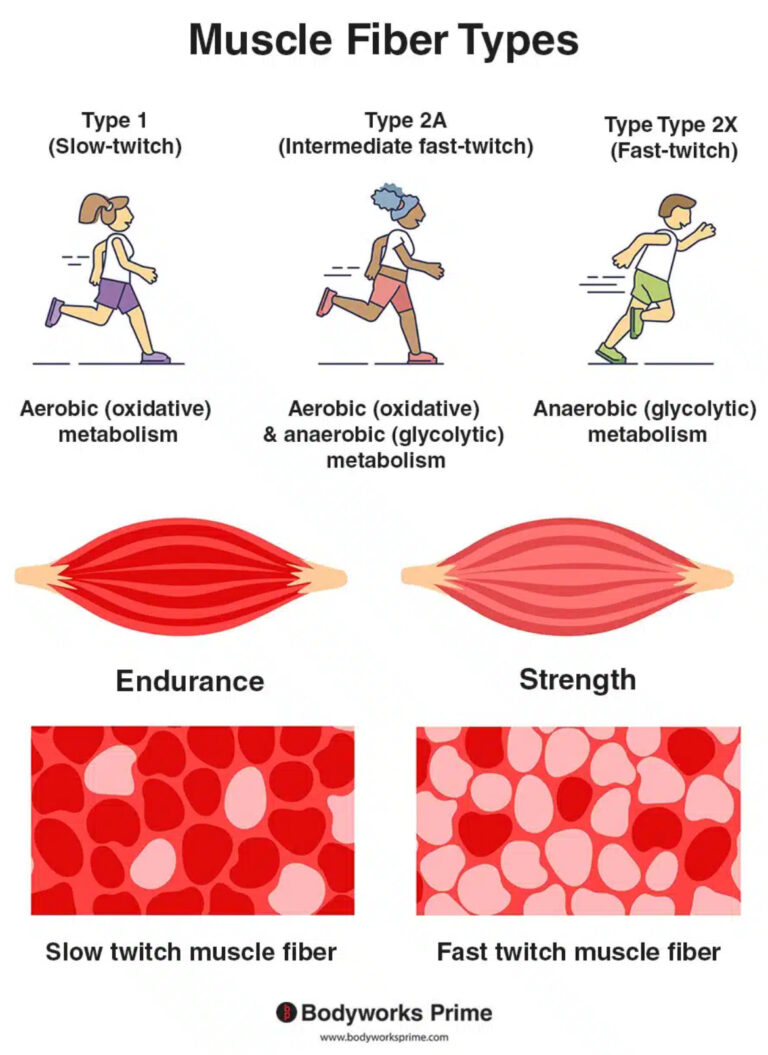

Weight training — also called resistance training — refers to exercises that cause your muscles to contract against an external resistance. That resistance can be a dumbbell, a barbell, a machine, a resistance band, or even your own body weight.

Physiologically, this practice stimulates muscle hypertrophy (growth), neuromuscular coordination, and metabolic adaptations that lead to higher resting energy expenditure (ACSM, 2022).

Unlike cardio, which primarily targets cardiovascular endurance, weight training reshapes your entire metabolism. Studies have shown that resistance training increases lean mass, decreases visceral fat, and helps maintain insulin sensitivity (Phillips & Winett, 2010).

Defining Your Objective

Every well-structured training plan starts with a goal. Your workout design will vary depending on what you’re trying to achieve:

- Fat Loss: Prioritize large muscle group exercises, moderate rest intervals (30–60 seconds), and compound movements to maximize energy expenditure. Combine with a caloric deficit.

- Muscle Gain (Hypertrophy): Use moderate loads (65–85% of 1RM), 6–12 repetitions, and controlled rest (60–90 seconds). Focus on progressive overload and volume (Schoenfeld, 2010).

- Conditioning and Performance: Include circuits, mixed modalities, and movement patterns that enhance stamina, agility, and coordination.

- Sports Performance: Your plan should mimic sport-specific demands — force, speed, and range of motion — integrating mobility and power training.

- General Health: A balanced combination of strength, mobility, and endurance work, two to three times a week, is enough to improve health markers and quality of life.

The Science of Workout Organization

A good workout isn’t random — it’s a carefully structured system. Let’s break down the foundations.

1. Exercise Order

Start with multi-joint (compound) movements — such as squats, bench presses, deadlifts, or pull-ups — which recruit more muscle mass and demand higher neuromuscular effort. Follow with isolation exercises (e.g., bicep curls, lateral raises) to target specific muscles.

Research suggests that performing complex exercises first leads to greater performance and training volume (Simao et al., 2012).

2. Types of Exercises

- Compound Exercises: Work several joints at once (squat, bench press, row). Ideal for building strength and coordination.

- Isolation Exercises: Target one joint or muscle (curl, triceps extension). Good for addressing weaknesses and improving symmetry.

- Bodyweight Movements: Push-ups, planks, or pull-ups are efficient for beginners or home workouts.

- Stabilization/Mobility Drills: Support posture and injury prevention, especially for sedentary individuals.

3. Main Muscle Groups and Example Exercises

| Muscle Group | Example Exercises |

|---|---|

| Chest | Bench press, push-ups, cable fly |

| Back | Deadlift, pull-up, bent-over row |

| Legs | Squat, lunge, leg press |

| Shoulders | Overhead press, lateral raise |

| Arms | Biceps curl, triceps extension |

| Core | Plank, hanging leg raise, cable rotation |

This division isn’t rigid, but it helps beginners visualize balance. A well-rounded program trains all major muscle groups at least once a week.

4. Frequency and Periodicity

For beginners, three sessions per week (full-body or alternating upper/lower) is a proven, sustainable structure. As you progress, you can increase to four or five sessions, focusing on specific muscle groups per day.

The key is consistency. Training adaptations — strength, muscle mass, endurance — depend on long-term, regular exposure to stimuli (Hickson, 1980).

A simple weekly schedule might look like:

| Day | Focus |

|---|---|

| Monday | Full Body A |

| Wednesday | Full Body B |

| Friday | Full Body A (variation) |

5. Intervals and Rest

Rest between sets depends on your goal:

- Strength: 2–5 minutes

- Hypertrophy: 60–90 seconds

- Endurance or Fat Loss: 30–60 seconds

Rest between workouts is equally vital. Muscle tissue grows during recovery, not during training. Sleep, nutrition, and stress control are non-negotiable elements of an effective plan (Dattilo et al., 2011).

The Psychological Side of Preparation

Training isn’t only about sets and reps — it’s about mindset. Starting a fitness journey requires building new habits, accepting gradual progress, and maintaining discipline through fluctuations in motivation.

Cognitive psychology suggests that implementation intentions (forming specific “if–then” plans, e.g., “If it’s 7 p.m., I go to the gym”) increase adherence to new behaviors (Gollwitzer, 1999).

Common Beginner Mistakes to Avoid

- Doing too much too soon (leading to fatigue or injury)

- Skipping warm-ups or cool-downs

- Ignoring nutrition and hydration

- Training inconsistently

- Not tracking progress

A workout journal or app can help you stay accountable and measure improvement over time.

Why Guidance Matters

Even though fitness information is widely available, tailoring a plan to your body type, experience level, and lifestyle requires expertise. An intelligent program balances science and practicality — just as Forge Biology does.

Our training consultancy helps you:

- Design a customized workout aligned with your goals and schedule

- Track measurable progress with evidence-based metrics

- Learn the “why” behind every exercise

Because fitness shouldn’t be a guessing game — it should be a science you can live by.

References

- American College of Sports Medicine. (2022). ACSM’s Guidelines for Exercise Testing and Prescription (11th ed.).

- Dattilo, M., et al. (2011). Sleep and muscle recovery: Endocrinological and molecular basis. Sleep Medicine Reviews, 15(3), 185–192.

- Gollwitzer, P. M. (1999). Implementation intentions: Strong effects of simple plans. American Psychologist, 54(7), 493–503.

- Hickson, R. C. (1980). Interference of strength development by simultaneously training for strength and endurance. European Journal of Applied Physiology, 45(2-3), 255–263.

- Phillips, S. M., & Winett, R. A. (2010). Uncomplicated resistance training and health-related outcomes. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, 42(5), 951–957.

- Schoenfeld, B. J. (2010). The mechanisms of muscle hypertrophy and their application to resistance training. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 24(10), 2857–2872.

- Schoenfeld, B. J., et al. (2019). Resistance training volume enhances muscle hypertrophy. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, 51(1), 94–103.

- Simao, R., et al. (2012). Exercise order in resistance training. Sports Medicine, 42(3), 251–265.

- Westcott, W. L. (2012). Resistance training is medicine: Effects of strength training on health. Current Sports Medicine Reports, 11(4), 209–216.

Forge Your Mind. Build Your Biology.

Join the Forge Biology newsletter — where science meets strength.

Every week, you’ll get:

-

Evidence-based insights on training, performance, and recovery

-

Real analyses of supplements that work (and the ones that don’t)

-

Deep dives into hormones, nutrition, and human optimization

No fluff. No marketing hype. Just data-driven knowledge to build a stronger body — and a sharper mind.

Subscribe now and start mastering your biology.